Infamy in Manila

Today is the anniversary of the attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines that brought the United States into World War II as a combatant. In Manila, reporters Melville Jacoby, Annalee Whitmore Jacoby, and Carl Mydans sprung into action to cover the conflict. Here's an excerpt from the book Eve of a Hundred Midnights, by Bill Lascher and published by William Morrow, describing their experience of that harrowing first day.

Shanghai Takes it On the Chin

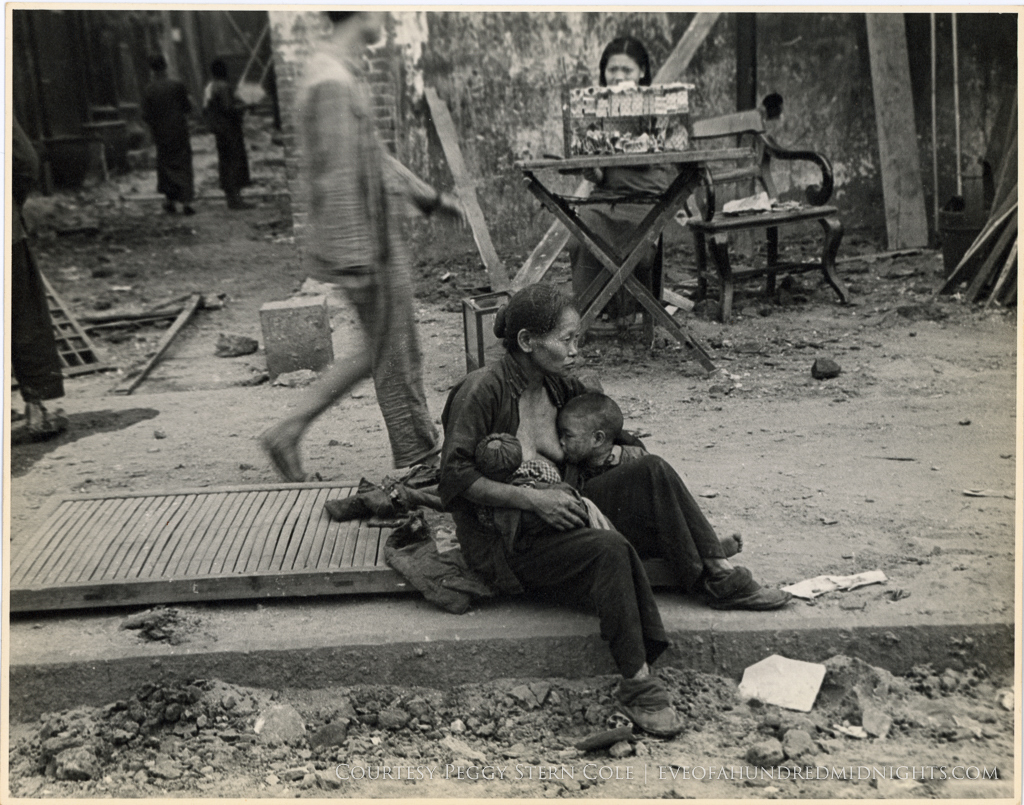

“I hate to see the rich kids in the cabarets, I hate to see the refugees, I hate to see the lousy foreigners in Packards and minks. Lots of money is being made now on the market and in business—but the Chinese peasant is taking it on the proverbial chin.”

Bombing Season

Three quarters of a century ago, today, at the height of “bombing season,” World War II correspondent Melville Jacoby took a brief break from his radio broadcasts for NBC, his writing and photography for Time and Life magazines to write to his mother and stepfather about life in wartime Chungking, or Chongqing, then the capital of China.

The Year that Changed Mel...And China

Melville Jacoby's interest in China can be traced back to 1936. That year and into 1937, during what would have been Mel's junior year at Stanford University, he went to China as an exchange student. There, he studied in the southern port city of Canton (that was the English transliteration of the time; it is now commonly transliterated as Guangzhou). He joined other American and Chinese students on the campus of Lingnan University (which still exists in another form in Hong Kong, while its original campus remains as part of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou).

Before and After. Wartime Chongqing as Captured by Melville Jacoby's Lens.

After spending four years with the research, writing and re-writing that shaped Eve of a Hundred Midnights, I feel sometimes as if I've lived in Melville Jacoby's shoes. At least, I feel as if I've seen the world through his eyes. As you can see in the following photos, Chongqing was a place of extensive striving and, after years and years of bombing — during his stints there in 1940 and 1941 Mel experienced 168 air raids — deeply scarred yet incredibly resilient.

Exploding Whales (Also, I Wrote a Book)

My head hurts. My carpal tunnels hurt. My blood is mostly coffee sludge. I've become a master of doctoring up Top Ramen. I know the shame that is ordering pizza from a place three blocks away because I can't be bothered to stand up because this sentence is connecting with that one and this with this one and oh my god I'm actually writing, there are words coming out and they make sense and I actually think I have something here and wow I'm going to win the pulitzer and.

When a Press Hostel is a Press Hotel

So, most of the journalists who worked in Chongqing during the war lived in the city's government-run "Press Hostel." When I was in Chongqing this spring I spent a great deal of time looking for the site of the hostel, and for years I have been researching everything I can about the place as I work on my book. Only just now -- as I make the last revisions on my book about Melville and Annalee Jacoby, who lived in the hostel -- did I think to type "Press Hotel" into google instead of “Press Hostel.” Oy...

When We Recognize Yesterday In Today

"Chaos has made wanderers out of 15,000,000 people. These people, not only Jews, torn from their homes will soon command the world's attention. For unless an intelligent situation is found, the dire effects of mass migrations will be felt over and over again during the coming centuries. It is hardly up to the refugees themselves. They are so completely befuddled that only happenstance guides their course."

A (Not So) Tiny Letter

I've been reading a lot of letters. It seems all I do these days is read letters.

But here's a letter for you. I wish I could send it to you on the onion-skin I so often find myself reading, the translucent sheets etched with the black ink of a an old Hermes's or Corona Portable's hammer-strikes, the sheet carefully folded into an envelope covered with bright stamps and decorated with a picture of a DC-3 and bold capitals reading "VIA AIR MAIL."

Of course, I can't, but I still want to say hello, because it's been a while (probably) and I miss you (certainly) and connecting beyond the superficial digital zones where we encounter one another. You may know where I've been, but perhaps something will settle on this screen. Letters, whatever their substrate, allow thoughts to steep better than ever-flowing streams of information we feel we must address and process now. Right now. Always now.

So feel free to read this and whatever letters follow at your leisure.

Mr. Lascher Heads to Washington

Just before Lascher departed for Washington, sources within the writer's temporal lobe confirmed that he continues to seek outside funding for his research and other expenses related to his telling of Jacoby's story. Lascher said he would welcome even a $5 contribution, though he's not ruling out the possibility that members of the public may contribute even more. Regardless of the amount he raises, the reporter says he'll expend whatever resources are necessary to research and recount Jacoby's tale.

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4