Come for the Book Cover and Release Date, Stay for the Food Poisoning

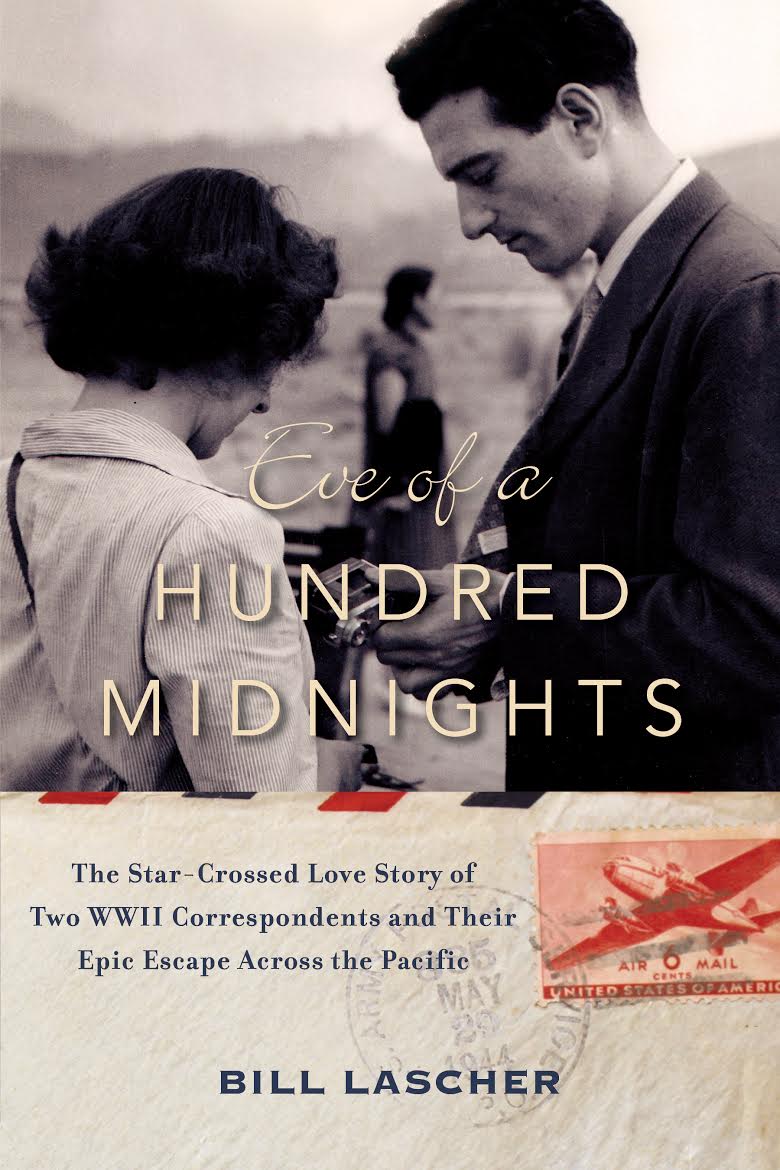

So, I could tell you a story about food poisoning and crazy rides across the Philippines, but I suspect you want to know what the cover of my book looks like, or what its final title and release date will be, or how you can pre-order it, or read about some fascinating characters from Portland who played both heroic and sinister roles in World War II.

Exploding Whales (Also, I Wrote a Book)

My head hurts. My carpal tunnels hurt. My blood is mostly coffee sludge. I've become a master of doctoring up Top Ramen. I know the shame that is ordering pizza from a place three blocks away because I can't be bothered to stand up because this sentence is connecting with that one and this with this one and oh my god I'm actually writing, there are words coming out and they make sense and I actually think I have something here and wow I'm going to win the pulitzer and.

The Last Night

A new year looms. As it has since I began unfurling this story, New Year's Eve carries a special meaning. As much as I'm thinking about Mel and Annalee, I'm also thinking about the people who left similar impressions upon them, and upon whom they left their own impressions. They are on my mind as I consider how, 73 years ago tonight, Mel and Annalee made the heartbreaking decision to leave their friends at a Manila hotel, run to the city's burning docks and leap aboard the last boat sailing into a dark, mine-strewn harbor before the Japanese entered the Philippines' capital. It was not an easy decision; the people they left behind were their colleagues, their friends, their fellow "soldiers of the press." They were, as I've addressed before, their tribe.

Allowing Sufficient Time

Around the corner from my house, inside the streetside window of a fancy spa, a slogan painted on an interior wall reads "Allow sufficient time." As the spa's clients emerge from their massages and saunas and wraps, the sign reminds them not to rush back into the world. It also reminds passersby like me not to rush through the world. I'm still trying to learn that lesson.

Framing My Travels

As much as I have to corral my writing and my research, I find if I have a camera in my hand instinct takes over. When I travel — whether across the country or across the city — I begin to see potential photographs framed everywhere I look. It's a delicate approach; one doesn't want to miss the moment in the search for memories of the moment. What's more? Some moments are meant to be transitory, to be fully experienced, not boxed by lenses and mirrors. Still, I've been enjoying photography as a counterpoint to my writing, and, since I often travel alone, the chance to share what I see with people I wish could be there with me (by the way, are you following me on Instagram?)

A (Not So) Tiny Letter

I've been reading a lot of letters. It seems all I do these days is read letters.

But here's a letter for you. I wish I could send it to you on the onion-skin I so often find myself reading, the translucent sheets etched with the black ink of a an old Hermes's or Corona Portable's hammer-strikes, the sheet carefully folded into an envelope covered with bright stamps and decorated with a picture of a DC-3 and bold capitals reading "VIA AIR MAIL."

Of course, I can't, but I still want to say hello, because it's been a while (probably) and I miss you (certainly) and connecting beyond the superficial digital zones where we encounter one another. You may know where I've been, but perhaps something will settle on this screen. Letters, whatever their substrate, allow thoughts to steep better than ever-flowing streams of information we feel we must address and process now. Right now. Always now.

So feel free to read this and whatever letters follow at your leisure.

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4