Infamy in Manila

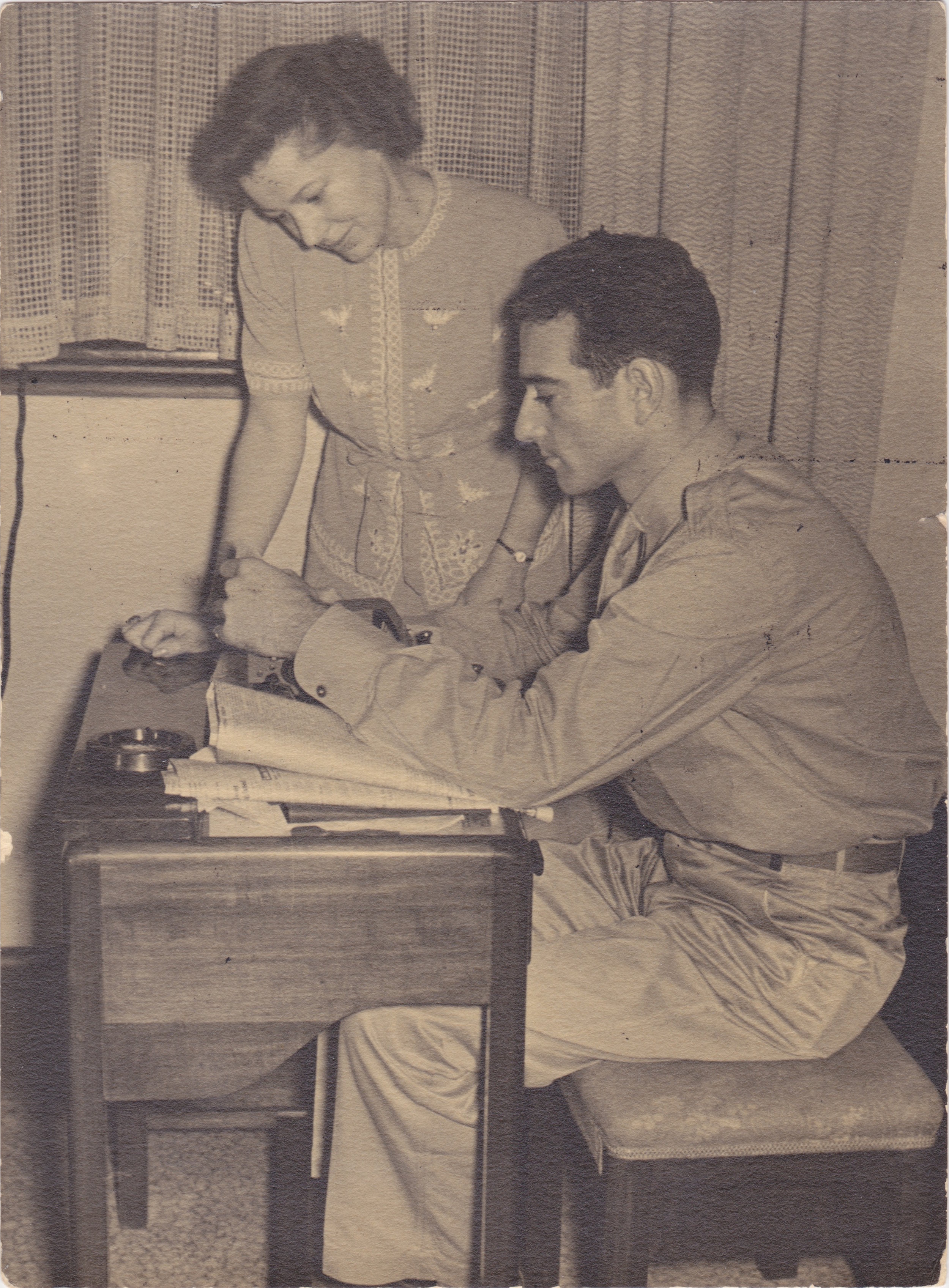

Newlywed reporters Melville and Annalee Jacoby at work together during the outset of World War II. Photo Courtesy Peggy S. Cole.

Communication lines with Hong Kong were silent.

Radios tuned to Bangkok broadcasts received dead air.

Wireless communications with the United States carried only static.

The streets outside the Bay View were empty.

The morning of December 8, 1941, was deceptively quiet. Then the phone rang.

It was Carl Mydans. Pearl Harbor had been bombed. A newspaper slipped under Carl’s door declared the news in bold headlines. Melville Jacoby didn’t believe his colleague, so he looked at his own paper and “saw some screwy headline that had nothing to do with Honolulu.”

Still doubtful about what Carl had told him, Mel went back to bed, but he couldn’t fall back asleep.

He called Clark Lee, who confirmed the news.

There had been ever-more-frequent Japanese flybys of the Philippines in the preceding days, but still, the news was a shock. “We’d known about the Japanese flights, all the other signs, but we didn’t quite believe it even out there,” Mel wrote.

While Mel was on the phone with Clark there was a knock at his door. He hung up and heard another knock, heavy and insistent. Mel found Carl standing outside the hotel room door, already dressed and ready to head into the city.

That World War II would be fought, and won, in the skies was clear early in the conflict. Though Japan delivered its first blows at Pearl Harbor, more than 6,000 miles across the Pacific from the Philippines, it followed its opening act with devastating raids on two airfields—Clark and Nichols Fields—in the Philippines. Two squadrons of B-17 bombers, dozens of P-40 fighters, and other planes were destroyed, eliminating much of the matériel that had been sent at General Douglas MacArthur’s request.

Despite the news of the attacks in Hawaii nine hours earlier, the planes had been left in the open while their pilots ate lunch nearby. Flyers didn’t receive warnings of the approaching Japanese planes until they were almost overhead.

“By noon the first day, pilots were waiting impatiently on Clark field for take-off orders to bomb Formosa,” Annalee Jacoby wrote, referring to the Japanese-occupied island now known as Taiwan. “Our first offensive action had to wait for word from Washington — definite declaration of war. Engines were warmed up; pilots leaned against the few planes and ate hot dogs.”

Twenty minutes later, without warning, Annalee wrote, fifty- four enemy bombers arrived, delivering a brazen, devastating raid on Clark Field that crippled an already underprepared American garrison.

These raids sparked a decades-long debate about who was responsible for the blunder, but whoever should be blamed, the United States lost fully half of its air capacity in the Philippines in this one devastating first day of the war.

“MacArthur’s men wanted to fight—but most of all they wanted something to fight with,” Mel wrote in a flurry of cables he sent Time following the war’s commencement and the air- fields’ decimation. Unfounded rumors of convoys and flights of P-40s coming to join the fight began almost as soon as the attacks subsided. They would not cease for months.

On that morning, Manila’s Ermita neighborhood was quiet. Mel arranged a car for the Time employees to share. Together they raced up Dewey Boulevard, to Intramuros, the walled old- town district that had been Spain’s stronghold during its 300- year occupation. When they reached the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) headquarters at 1 Calle Victoria, they found MacArthur’s driver, who had arrived early in the morn- ing, asleep in his car.

“Headquarters was alive and asleep at the same time,” Mel wrote. MacArthur’s staff was weary-eyed but busy as they girded for war. Within hours, helmeted officers carrying gas masks on their hips raced back and forth across the stone- walled headquarters, stopping only briefly to gulp down coffee and sandwiches. The general himself was his usual bounding self, striding through the headquarters as staff and other wit- nesses confirmed reports of attacks throughout the Philippines. Mel and Carl were concerned about their jobs. Would wartime censorship clamp down on their reporting?

“The whole picture seemed about as unreal to USAFFE men as it did to us,” Mel later wrote. “We couldn’t believe it, and MacArthur’s staff had hoped the Japanese would hold off at least another month or so, giving us time to get another convoy or two in with the rest of the stuff on order.”

This hesitation, of course, was partly to blame for the devastation that occurred that day and the unsettled footing with which American forces fought during the brutal months to come.

Meanwhile, deep-seated racial prejudices kept many Americans from believing that Japan was capable of carrying out the attacks.

“Those days were eye-openers to many an American who had read Japanese threats in the newspapers with too many grains of salt tossed in,” Mel wrote. “They still couldn’t believe the yellow man could be that good. It must be Germans; that was all everyone kept saying. We were just beginning to pay for years of unpreparedness. The shout ‘It’s Chinese propaganda’ had suddenly lost all traces of plausibility.”

Regardless of who was to blame, U.S. forces reeled.

Manila was quiet even as chaos engulfed the headquarters, where a scrum of reporters waited for updates. Rumors flew beneath the shady trees of Dewey Boulevard, rippled up the Pasig River, and raced past the storefronts along the Escolta.

“The whole thing has busted here like one bombshell, though, as previous cables showed, the military has been alert over the week,” Mel would soon write.

As the realization of what had begun set in, Manila residents rushed through the city, withdrew cash from banks, stocked up on food, and bought as much fuel as they could before rationing was ordered. Businesses quickly transformed basements into bomb shelters. Sandbags became scarce. As would happen all over the United States, local military rounded up anyone of Japanese descent, whether they were Japanese nationals or not. The Philippines waited for war.

From Eve of a Hundred Midnights, by Bill Lascher and published by William Morrow (2016). For the story of the Jacobys' last-minute escape from the Philippines and to learn about their work as war correspondents in China and the Philippines, find Eve of a Hundred Midnights at your favorite bookseller, or order it from Indiebound, Powell's, Amazon, or Barnes & Noble.