A (Not So) Tiny Letter

I've been reading a lot of letters. It seems all I do these days is read letters.

But here's a letter for you. I wish I could send it to you on the onion-skin I so often find myself reading, the translucent sheets etched with the black ink of a an old Hermes's or Corona Portable's hammer-strikes, the sheet carefully folded into an envelope covered with bright stamps and decorated with a picture of a DC-3 and bold capitals reading "VIA AIR MAIL."

Of course, I can't, but I still want to say hello, because it's been a while (probably) and I miss you (certainly) and connecting beyond the superficial digital zones where we encounter one another. You may know where I've been, but perhaps something will settle on this screen. Letters, whatever their substrate, allow thoughts to steep better than ever-flowing streams of information we feel we must address and process now. Right now. Always now.

So feel free to read this and whatever letters follow at your leisure.

Journalism of the Unknown Unknowns

It's complicated ... and that's the point. Journalism doesn't have all the answers, and we shouldn't expect it to. We shouldn't expect our stories to solve things for us.

Journalists' primary role is not to answer the challenges that face our society: it's to bring light to those challenges, so that those with the proper tools to solve a given problem will know that the challenge exists. In a sense, we're brokers, we're middle-men, we're matchmakers between problems and solutions. But those problems and solutions still have to get to know one another, find the right match. We can't consummate their relationships, we can just help them find one another.

Heart of the Monster: Journey to SEJ 2010, Part 3

I admit that the story – and this entire series, delayed as it may be – has meandered from its path. Nevertheless, I'm also wrestling with how to respond honestly to my experiences, with what happened in my brain on the journey and whether it's self-indulgent to serve this soup of thought (it's a little too stagnant to call it a stream) to you, instead of a straightforward report of the who and the what I saw where and when. Which approach provides the real, honest reporting?

Roads traveled, stories unraveled

For the next week or so, each day I'll recount some element of my October trip to and from the 2010 Society of Environmental Journalists conference. I'll combine my recollection of what I saw, experienced or learned, tweets I made at the time, photographs and links to some of the cool things I learned. Check back each day for new reflections, tales and reports. At the end of my updates I'll post a link to read the story as one narrative (and post a complete photo album as well). Be prepared. This series will include a mix of storytelling styles -- don't expect straight journalism, or complete creativity. In fact, don't expect anything but a journey. More than two months after I've returned from one journey, though, I've yet to trace its path. I still haven't traced my trip from Portland to Missoula and back, and I can't quite express why not. Perhaps I don't feel like the trip's over, like I've truly returned. Perhaps I can't record it until I've described it, until I've wrapped the journey in words and pictures and recollections that I realize are fading with each day.

Some of you might not be interested in such ponderings.

“Get to the point,” you'll say. “Tell me about the conference. Tell me what you learned, what you saw along the way, what the latest news is. I only have so much time. Don't you know attention spans are ever so slight? Haven't you ever heard of an editor?"

Indeed I do, and I have. As I've noted elsewhere, as so many have noted before, though, to truly travel you can't simply move from Point A to Point B. You can't experience this world's multiplicity of dimensions through a straight line.

The truth is, of course, I did wait to write this down. I let the story fester. I let it fall away and apart. Like anyone might, I've been making excuses for months now for not chronicling my trip. My terrible cold on the road. Assignments due just upon my return. Job applications. Novel Writing. Story development. Other conferences to attend as a reporter. Holidays. I could think of any number of reasons why you're reading this now, today, this very second, and only now, but this is the moment, this is when these words take shape.

Following a War Correspondent's Footsteps to the Oil Spill

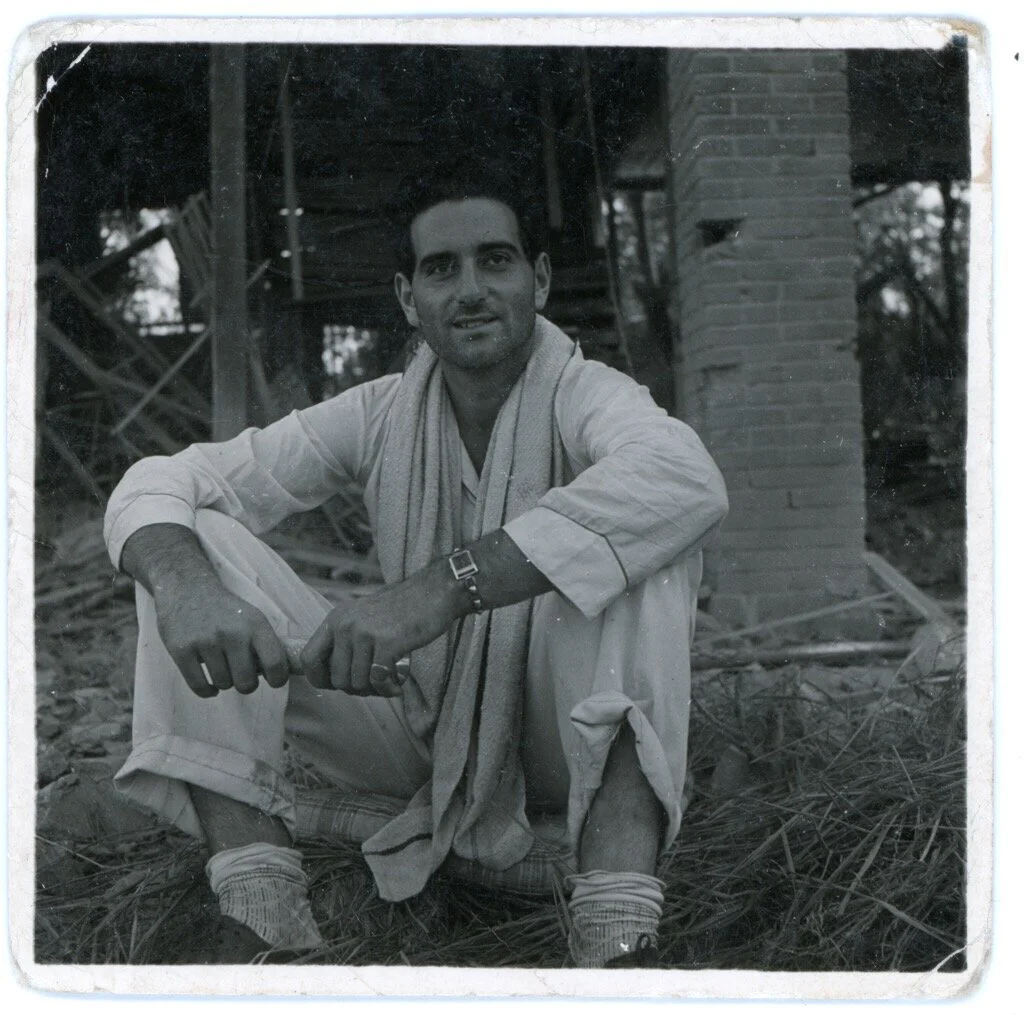

Will following the footsteps of Melville Jacoby, a World War II correspondent and my grandmother's cousin, help me cover the gulf oil spill?

As I learned from my grandmother about Melville, I realized he played a central role telling stories about one small part of another great, global crisis. Perhaps the war was more romantic than seemingly glacial environmental changes (though really, they aren't so glacial) but both crises are the defining milieus of a particular generation. "Like Melville," I wrote, "I want to chronicle my generation's response to its crisis."

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4