Opting Out of Journalism's Race to the Bottom

If we're discussing issues like what it costs to inform the public about housing and homelessness, or awe-inspiring scientific discoveries, does it matter who makes the impact, when what matters most is whether as many people as possible hear it?

On Protest and Reporting

Today, Poynter ran a piece titled "Should journalists protest in Trump's America?" It was mostly focused on newsroom journalists. In reply, I wrote up my thoughts about how it applies to me as a freelancer.

The Best Freelancing Advice I've Seen

If you're just starting out as a freelance writer -- hell, if you're well-established as a freelancer -- I strongly urge you to read this piece by Scott Carney, a Colorado-based investigative journalist and anthropologist. In the piece Carney suggests freelancers abandon the long-held practice of "silo" pitching, wherein writers pitch articles to one outlet at a time and rather take their publications out to multiple editors simultaneously.

Following a War Correspondent's Footsteps to the Oil Spill

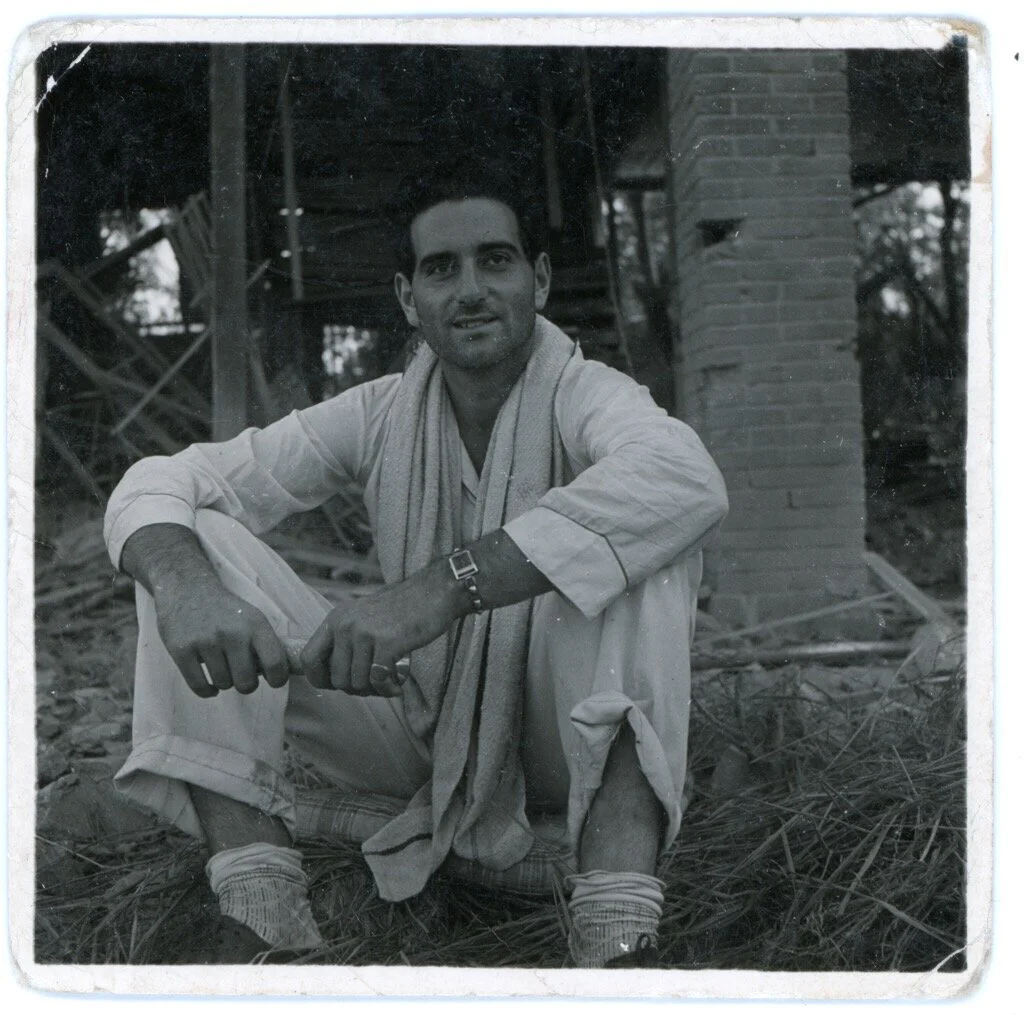

Will following the footsteps of Melville Jacoby, a World War II correspondent and my grandmother's cousin, help me cover the gulf oil spill?

As I learned from my grandmother about Melville, I realized he played a central role telling stories about one small part of another great, global crisis. Perhaps the war was more romantic than seemingly glacial environmental changes (though really, they aren't so glacial) but both crises are the defining milieus of a particular generation. "Like Melville," I wrote, "I want to chronicle my generation's response to its crisis."

Making the most of making the media

For all the critiques I have of the We Make the Media Conference at the University of Oregon's Turnbull Portland Center in November, 2009,and all the many more already so eloquently articulated by other thinkers (Click here for a list of the reflections I've found, some of which I'm responding to here), I'm stunned by how, a few days later, I remain invigorated by the event. Like Abraham Hyatt and many others, I left the event quite drained, but now feel energized. Though the event may not have gone in the direction organizers hoped, perhaps it was a success anyhow.

The eyesore, history and the untold story

What are we really protecting? We have a great deal of unsold housing stock. Oxnard has buildings that already exist. Ventura County has miles upon miles of substandard homes and poorly utilized space. What if we spent the same time, the same money, the same energy and investment and subsidies we would put into new projects on instead reconstructing the cities and communities and neighborhoods that already exist? What if we brought our county, and our country, back to life?

A life, a career, a world repurposed

When I applied to USC more than a year ago I wrote about how the shifting environment is fast becoming a global story, possibly the only global story, a point similar to one recently argued by Bill McKibben and other journalists. Back in the Spring of 2008 I argued that whether one accepts climate change as a preventable human crisis, or disagrees that it is a threat (or is caused by human activity), the mere discussion of the environment has global and local implications. If a shipping company invests in more efficient cargo jets because it expects to save money by stretching its fuel spending or does so because it perceives a public relations boost, that company is making a decision with tremendous impact on the environment. At a more local level, the city resident who uses a combination of bikes and mass transit to get to work because she realizes the reduction in her carbon footprint, or because she just cannot afford to purchase a car, will affect the environment either way. There is a difference in scale, but the outcome of either decision will impact many beyond the company and the young woman, altering the experiences and decisions of those additional parties.

Trial by Blogger

When suspects are treated in the media as guilty from the moment of their arrest, it not only affects the quality of the jury pool, it also increases the dissonance the public feels when a jury, examining the facts and arguments presented by both sides in a trial, does not side with the prosecution. The more the public feels our legal system "protects" criminals or otherwise carries unexpected consequences, the less able it is to operate effectively and fairly. This legal system, while imperfect, is the core of our democracy as we know it, and we should work to fix its flaws, ensure its fairness, and remain committed to the ideals of justice we purport to believe in.

Undercutting the competition

If publishers and other hiring managers want to succeed, they will need a committed, loyal and stable staff, and they must develop sharp, insightful contributors. An investment in skilled journalists ready to take risks to lead publications into the future is a wise choice. It may seem counter-intuitive to talk about investment in a time of economic malaise, but those who take such leaps of faith will be best positioned for future success. Those, however, who treat their content producers as chattel will continue to struggle to maintain a stable source of original content, and thus, they will spend all their time watching editors and writers leave for greener pastures while their competitors invest in competent, devoted teams passionate about the work their doing and the success of their organizations.

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4