One Last Assignment One More Time

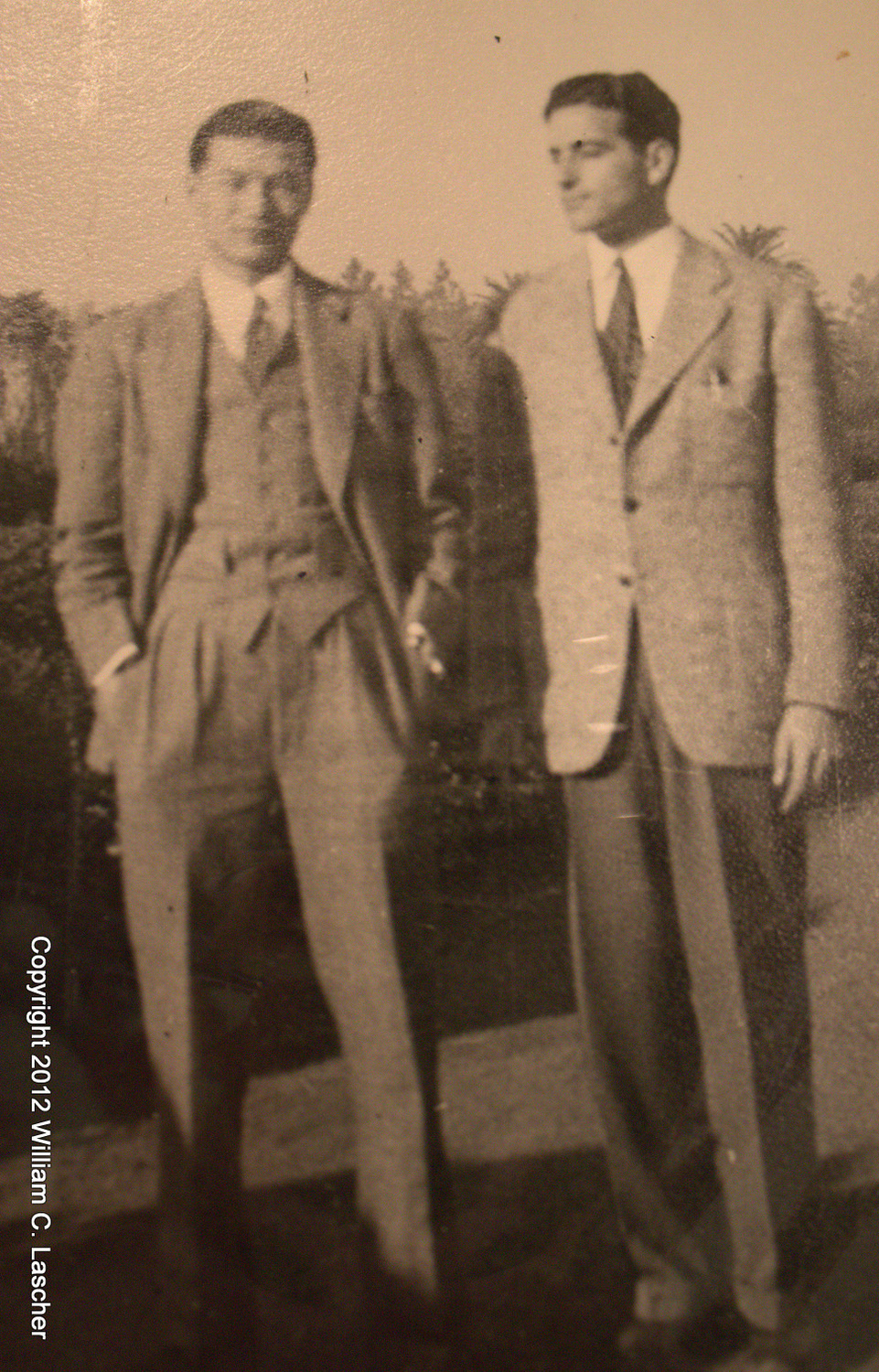

After much anticipation, last week I released a new video describing Melville Jacoby's fantastic life. It also reintroduces the work I'm doing to tell his story. Click the photo in this post or the link below to view it. I'm really proud of this video. I'd love to hear your opinion and for you to share it with anyone interested in wartime journalism, storytelling, or 1930s and 40s nostalgia. Meanwhile, I'm preparing for a trip to Southern California to meet one of Mel's friends from his time as an exchange student in China. I'm so fortunate he's still around, and willing to speak with me. I'll also be visiting my grandmother to properly review and inventory her collection of materials from and related to Mel's life. Keep reading to learn what I'm up to.

After much anticipation, last week I released a new video describing Melville Jacoby's fantastic life. It also reintroduces the work I'm doing to tell his story. Click the photo in this post or the link below to view it. I'm really proud of this video. I'd love to hear your opinion and for you to share it with anyone interested in wartime journalism, storytelling, or 1930s and 40s nostalgia. Meanwhile, I'm preparing for a trip to Southern California to meet one of Mel's friends from his time as an exchange student in China. I'm so fortunate he's still around, and willing to speak with me. I'll also be visiting my grandmother to properly review and inventory her collection of materials from and related to Mel's life. Keep reading to learn what I'm up to.

Discovering One More Friend of Melville Jacoby's

By now, anyone closely following Melville Jacoby's story knows a little bit about Chan Ka Yik. Last week, a few members of my family and I met Chan's daughters for something of a reunion between our two families. As I've already described, that was itself was a lovely experience. But Chan was not Mel's only friend in China, nor was he the only Chinese man Mel met who later moved to the United States. My visit to Palo Alto also stirred up a fantastic coincidence. This is the sort of thing that can provide a completely different glimpse three quarters of a century in the past. Click the link to read about that coincidence, and to hear the fantastic discovery I made as a result of that visit.

Won't You Be My Mrs. Luce?

"He was you at that stage of the game," my grandmother said. "It was a different way, but that's a story too. How does a young reporter like Bill Lascher get started?"

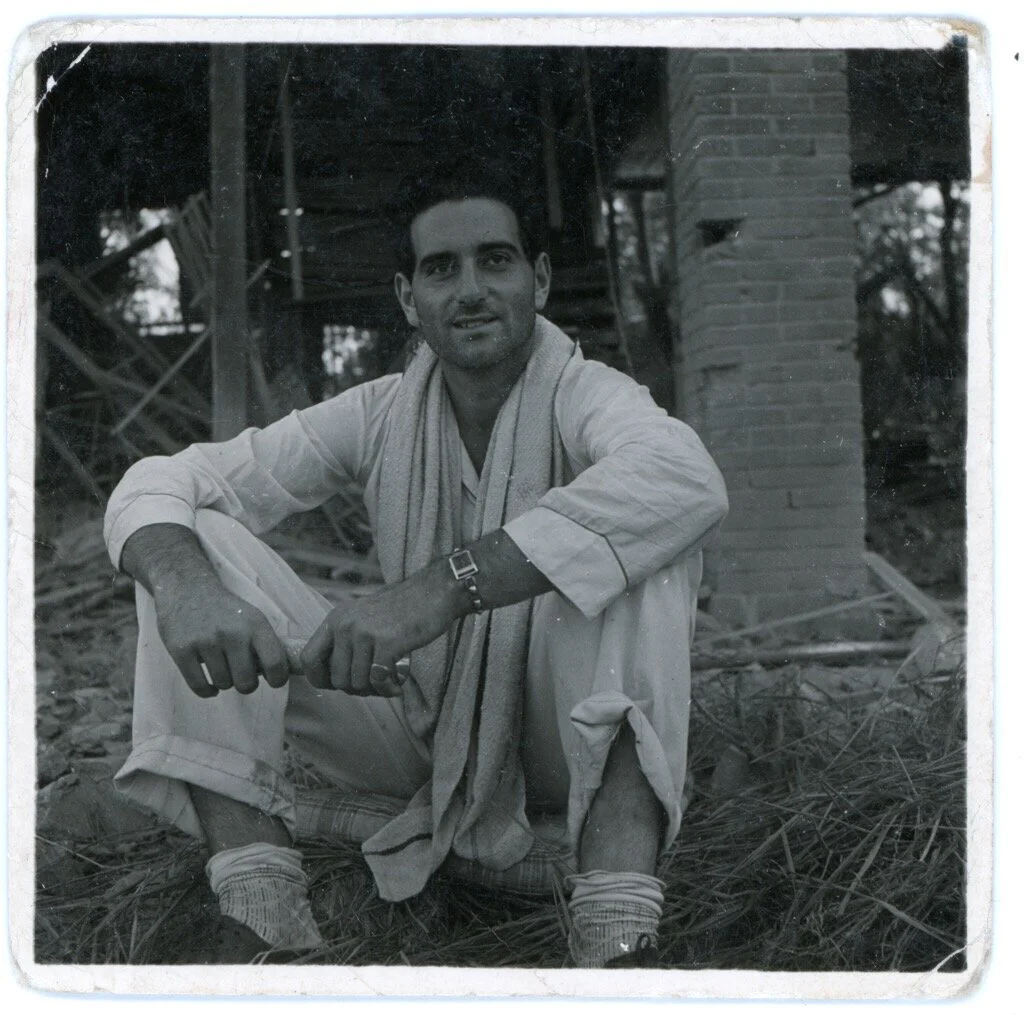

This is how. By not letting go. Two weeks ago I completed a quarter teaching a community college class on multimedia journalism and turned in the last of two small freelance assignments on my plate. All that's left for me is what I'm doing now: throwing all that I have on the table in pursuit of this one last assignment. Everything I have, everything I can be is now focused on this account of the first Time Magazine reporter killed in the line of duty, this tale of Melville Jacoby, this story of my family's beloved cousin and this man who lived so fantastically before he died so tragically.

"He was you at that stage of the game," my grandmother said. "It was a different way, but that's a story too. How does a young reporter like Bill Lascher get started?"

This is how. By not letting go. Two weeks ago I completed a quarter teaching a community college class on multimedia journalism and turned in the last of two small freelance assignments on my plate. All that's left for me is what I'm doing now: throwing all that I have on the table in pursuit of this one last assignment. Everything I have, everything I can be is now focused on this account of the first Time Magazine reporter killed in the line of duty, this tale of Melville Jacoby, this story of my family's beloved cousin and this man who lived so fantastically before he died so tragically.

"He had the good luck to be on an airplane with Mrs.[Clare Booth] Luce [the wife of Time Magazine founder Henry Luce, who was also on that plane], who was impressed with him." my grandmother said. "You have to be on an airplane with someone who will be impressed with you."

This is Our War

This month marked the beginning of my full-time focus on Melville Jacoby. June marked my latest birthday. May marked three years since I received my master's degree.

In many ways I haven't lived a normal life since.

This month marked the beginning of my full-time focus on Melville Jacoby. June marked my latest birthday. May marked three years since I received my master's degree.

In many ways I haven't lived a normal life since.

I'm 32. My last "normal" job ended four years ago, and only three years since I started my first full-time position in my chosen profession. Let that sink in. Less than 10 percent of my time on this Earth has been spent in a professional workplace. The vast majority of my life has been spent not working on my career, not plugging away in an office day-in and day-out, not doing what I thought "it" was all leading toward. Life so far has seemed more about creating and recreating myself. It has been about making something of myself rather than actually being something.

And here I am trying to write a book about someone else, trying to tell someone else's story. The something I am making of myself depends on the something Melville Jacoby made of himself, and of the something of his that was denied.

And it was denied when Mel was just 25. That's the same age I was when I got that first "real" job. By that time Mel had made friends around the world. He'd dodged bullets. He'd made daring escapes. He'd met and impressed some of history's most prominent figures. He'd completed his education and made his way into a fantastic job. He'd been a heartthrob, he'd loved and lost, and, finally, he'd married an astounding woman.

Mel's life was short, but full. When I compare it with mine, it's difficult not to feel something missing. I wonder if that sense of disappointment is of my own making or a product of this era.

A Reunion of Sorts

California, here I come, right back where I started from. In a little less than two weeks I'll hit the road for Palo Alto, California, the home of Stanford University. That's where Melville Jacoby earned his bachelor and master's degrees in the 1930s (it's also where his wife, Annalee Whitmore Jacoby Fadiman was the first female managing editor of the daily student newspaper and where other close friends, such as Shelley Smith Mydans, studied). It's a trip I've long been waiting for, and one that wouldn't be possible without the support, encouragement and financial contributions I've received since I first launched my Kickstarter campaign and then launched the current fundraising campaign. Yes, I'll be retracing Mel's footsteps and digging through archives, but I'm most excited for what might best be described as a reunion when we meet the children of Mel's best friend from his time in China ...

Following a War Correspondent's Footsteps to the Oil Spill

Will following the footsteps of Melville Jacoby, a World War II correspondent and my grandmother's cousin, help me cover the gulf oil spill?

As I learned from my grandmother about Melville, I realized he played a central role telling stories about one small part of another great, global crisis. Perhaps the war was more romantic than seemingly glacial environmental changes (though really, they aren't so glacial) but both crises are the defining milieus of a particular generation. "Like Melville," I wrote, "I want to chronicle my generation's response to its crisis."

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4