Where should green planning efforts come from?

Hundreds of urban planners, architects, developers, environmentalists, entrepreneurs and policymakers danced around this question last week as they convened on Portland for the second annual Ecodistricts Summit.

Hosted by the Portland Sustainability Institute (PoSI), the event complements a maturing experiment to make five of the Oregon metropolis's neighborhoods into "Ecodistricts," neighborhoods designed to be more sustainable.

A Renter's Market?

For the first time in decades it's cool to be a renter. So why is it so hard to rent a home and still be “green"? This week, as news outlets across the board reported a steep decline in home sales and prices in July, especially in the West, some reported increased preferences for renting, especially with the added uncertainty wrought by high unemployment levels. Particia Orsini of AOL's Housing Watch reported Aug. 26 that Americans, particularly homeowners, are now more likely to think that renting a home is more prudent than buying one. Other news outlets, such as Forbes and the Real Estate Channel and Time's “Curious Capitalist" blog, also recently dissected the growing preference for renting.

Orsini cited statistics from Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies. I took a glance at that report – titled State of the Nation's Housing 2010 – and found it shows that rental vacancies grew from 2006 to 2009, even though the renter pool was growing at the same time. In fact, U.S. Census Bureau housing vacancy survey data cited by the report shows that fewer people own homes in the West compared to any other region in the nation. The same numbers also show that nearly three-quarters of white Americans own homes while fewer than half of minority populations do.

So, what does this all have to do with the environment?

Ducking the Elephant in the Room

The day takes shape slowly. Getting out the door just happens. Once you do the bus is ten minutes late. Then, so is the MAX, but you don't mind. You've been quietly extricating yourself from time. You wait in the chill beneath an interstate, listening to teenagers gossip. Staring at the spikes lining the steel beams beneath the roadway you think perhaps a bit too long about pigeon deterrence.

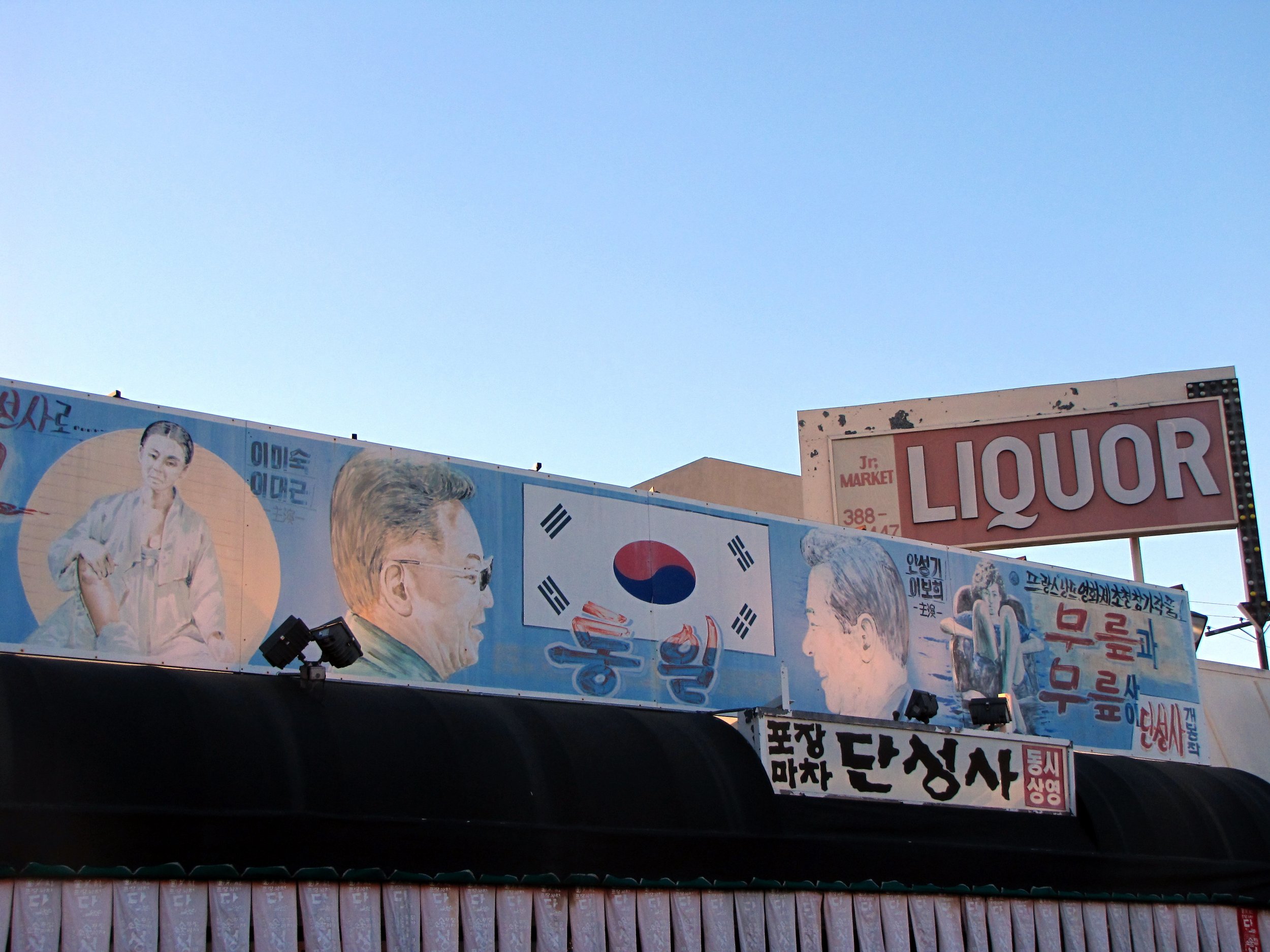

Koreatown's sign language

This afternoon I ran an errand a couple Purple line stops away. It was such a beautiful day that instead of taking the subway I decided to meander home on foot. Fortunately, before I left the house I thought to grab my camera. I took the opportunity to look around a bit and capture some of my favorite signage and guerrila art in Koreatown. Note Kim Jong-Il's appearances. Guess at which point my sense of humor turned a little juvenile.

What it's like - In transit through L.A.

As the street lamps and billboards and taillights fade into the darkness I slip away from the Los Angeles I know, jostled into a new awareness by the thought of the path I am threading through the urban fabric.

I find myself all over the world…Familiar memories vector across my neural network, stitched together to form my life, as has begun to happen here, where I left my car at home, here, in L.A., the supposed Eden of automobiles.

Rearranging Our Pieces, Playing With Our Future

Is our imagination so limited that we think anyone will survive by doing the exact same thing we've done for half a century? Why can't we take the same simple wonder of an afternoon of play and build a new world with the pieces we already have? Why can we not take our bricks and track and blocks and rearrange them, as we did countless times as children, into new buildings, new cities and new transportation networks? Why can't we put our architects to work redesigning the decrepit spaces that already pepper our world? Why can't we put builders to work reconstructing our destroyed communities? Why must we mine new materials and continue the urbanization of our wild lands when so much unused housing stock and other structures sit vacant?

Why can't we rearrange the pieces we already have? If we could do it endlessly as kids, we really can do it now.

Landings

Portland proper, if not its suburbs, swirls with the pot luck attitude of a true community, although strong, valid critiques exist of redevelopment within the city as well. Far more than any place I’ve been in the United States except perhaps, as a matter of fact, the original Portland, this is a self-determined city, including the blemishes of its modernity.

As I land and swirl through so many past worlds of mine, I remember I can move about the city without thought. However, I’m still constantly discovering more beneath Portland's surface. The only time I ever had a similar sensation was at my five-year college reunion last year, and that feeling was aided by the presence of so many others who had experienced that period of my life with me. But where the grounding I find among my undergraduate peers is most firmly rooted in a mindset, there seem to be physical roots here in Portland.

Adaptive Reuse: Parking Meters to Bike Racks

Some readers may know I'm working on a magazine-length news feature exploring the opportunities to change transit behaviors, policies and infrastructure in Los Angeles given the constraints of current resources, technology and politics. I'm most interested in what steps can be taken to permanently change how people move about the region. One thing I'm learning and hearing from others is that a crucial reaction to our economic and environmental crises is to effectively reuse, redeploy and repurpose the infrastructure and materials we already have available to us.

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4