Following a War Correspondent's Footsteps to the Oil Spill

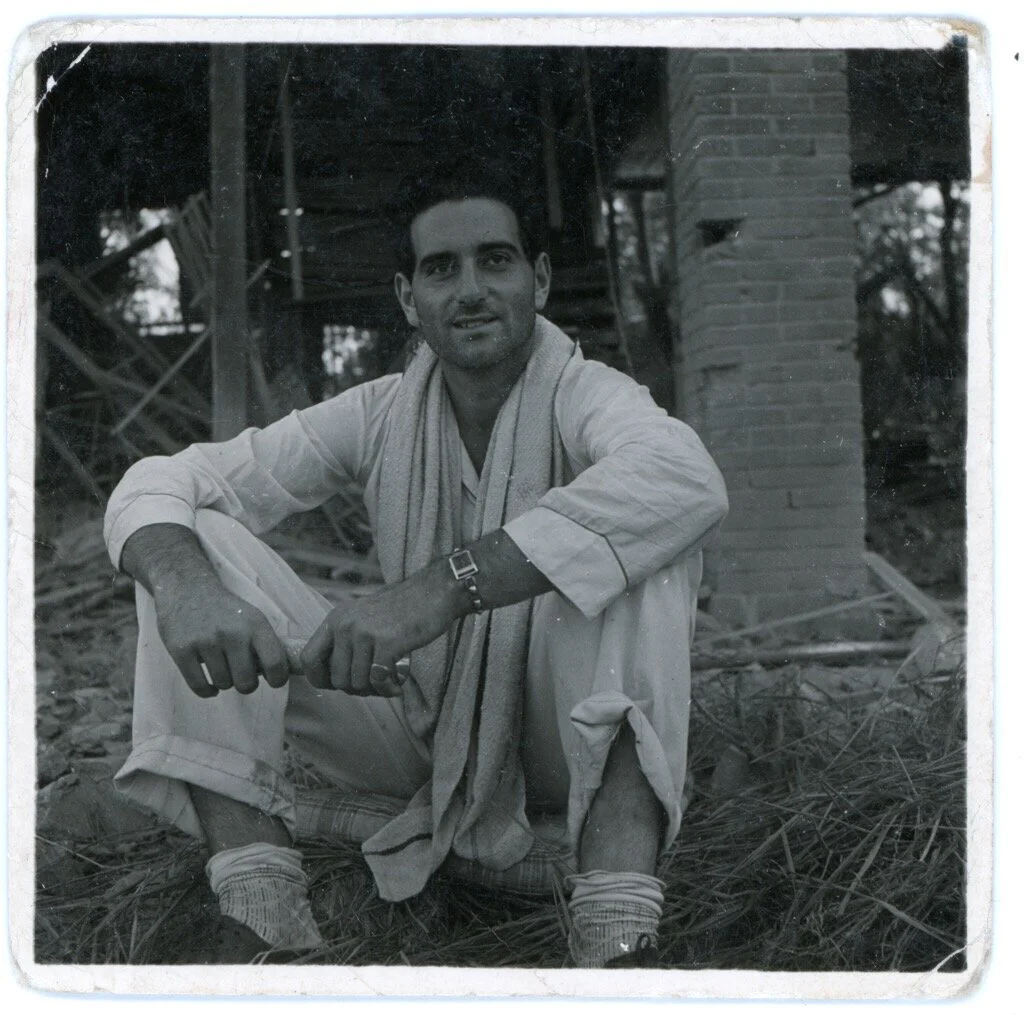

Will following the footsteps of Melville Jacoby, a World War II correspondent and my grandmother's cousin, help me cover the gulf oil spill?

As I learned from my grandmother about Melville, I realized he played a central role telling stories about one small part of another great, global crisis. Perhaps the war was more romantic than seemingly glacial environmental changes (though really, they aren't so glacial) but both crises are the defining milieus of a particular generation. "Like Melville," I wrote, "I want to chronicle my generation's response to its crisis."

Mt. Wilson Observed

As important as the landscape and the history is, I know two families have been shattered by the loss of the firefighters who perished, and I realize there are at least dozens more whose lives have been permanently changed by the loss of their homes. I'll treasure those men's sacrifice fighting to save this place that, in just two short slivers of time, meant so much to me.

Search Posts

Archived Posts

- March 2024 1

- October 2023 1

- October 2022 2

- December 2017 1

- April 2017 1

- February 2017 1

- January 2017 1

- November 2016 2

- August 2016 2

- July 2016 2

- December 2015 1

- November 2015 2

- September 2015 3

- April 2015 1

- March 2015 1

- February 2015 1

- January 2015 4

- August 2014 1

- May 2014 1

- April 2014 4

- March 2014 6

- December 2013 1

- November 2013 1

- August 2013 3

- May 2013 2

- April 2013 1

- December 2012 3

- November 2012 2

- October 2012 2

- September 2012 3

- August 2012 6

- July 2012 4

- June 2012 1

- May 2012 6

- April 2012 2

- March 2012 3

- January 2012 2

- September 2011 2

- August 2011 2

- July 2011 1

- May 2011 9

- April 2011 2

- March 2011 1

- January 2011 2

- November 2010 1

- October 2010 1

- August 2010 3

- July 2010 1

- June 2010 1

- May 2010 12

- April 2010 2

- March 2010 1

- January 2010 1

- December 2009 1

- November 2009 4

- October 2009 2

- September 2009 2

- August 2009 1

- July 2009 1

- June 2009 4

- May 2009 1

- March 2009 5

- February 2009 4