In the fall of 2002, writer Bill Lascher and photographer Whitney J. Fox, spent three months visiting Jackman, in rural Maine, and chronicled this border town as seen through the eyes of the wilderness guides, loggers, construction workers, tourists, adventurers and drifters who gathered at its "community office," the Northland Hotel.

Northland

Words: Bill Lascher | Photos: Whitney J. Fox

Telling Jackman's Story

In the fall of 2002, while attending the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies, photographer Whitney J. Fox and I spent three months in the rural border town of Jackman, Maine and the landmark Northland Hotel. Throughout the past century the Northland has brought together townspeople, wilderness guides, loggers, construction workers, tourists, adventurers and drifters in a sort of "community office." Through conversations with Northland regulars and guests, Whitney and I learned the nuances of a small community, its dependence upon the surrounding wilderness, and how shifting forest management practices, rural lifestyles, economic strain and cultural shifts have shaped the region (These influences continue to shape rural Maine - and regions like it - to this day.)Part I: The Community Office

THE NATION is on Orange Alert.

In north-central Maine, thick forests blur the line separating the United States from Quebec. The only indication that the border exists is a small government checkpoint surrounded by a seemingly endless expanse of wilderness. Curious about what life must be like at the edge of America when national security is on the tip of everyone’s tongue, I head to the border one late-September afternoon.

Government officials manning the Port of Entry have little to say to me. It’s difficult to tell if they’re quiet because of the new alert, or because they’re new transfers unfamiliar with the region. Nonetheless, they make an attempt to be helpful and suggest I track down one man, Sherby Paradise, who lives sixteen miles south in Jackman and is bound to have more to say about the region.

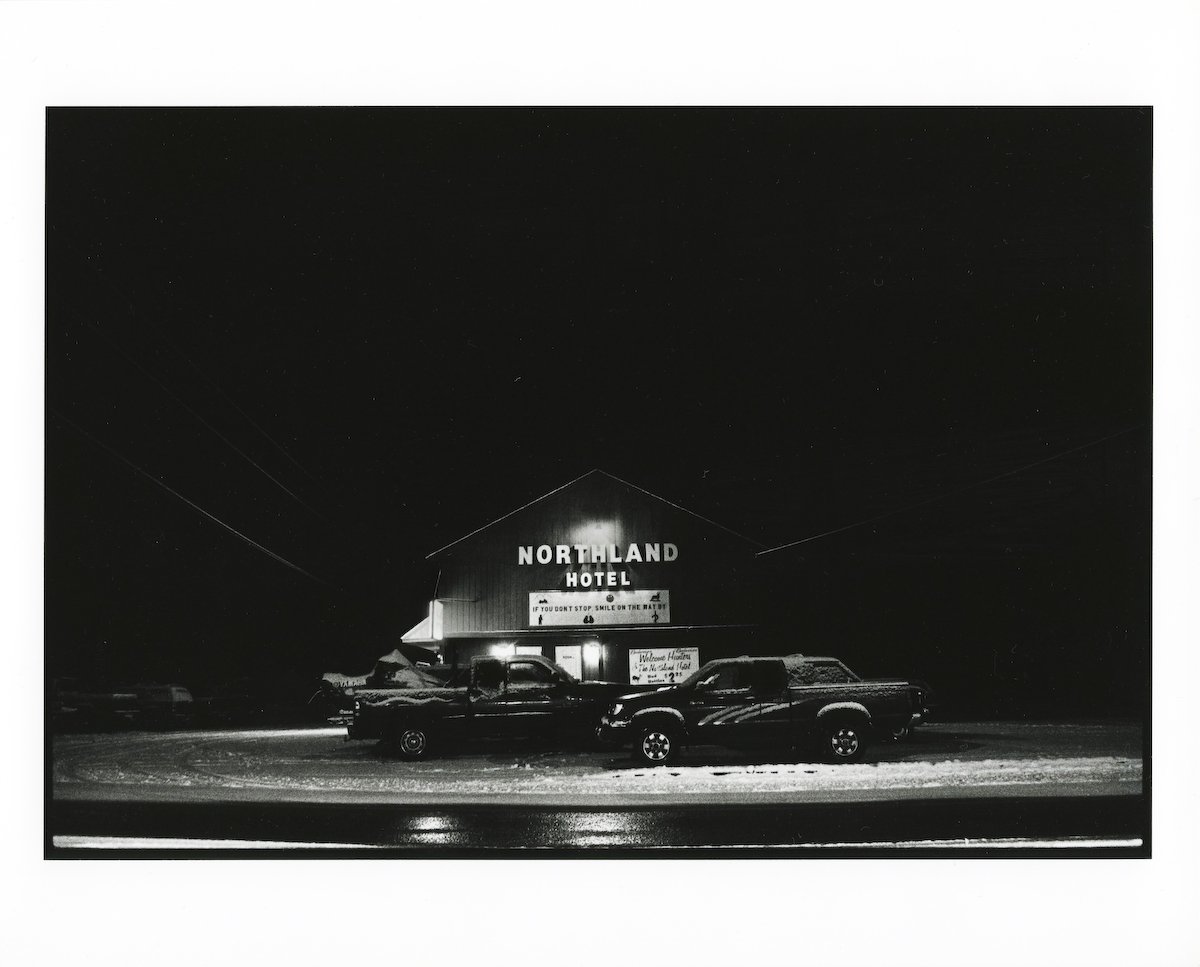

Searching for Sherby Paradise, I discover the Northland.

I discover strong friendships and traditions in a wilderness on the verge of destruction. I discover hospitality in a town bracing itself against outsiders.

Jackman doesn’t fear foreign terrorists. It fears domestic tourists. The same influx that breathes life into the town will be the force that changes it forever.

For now, life goes on much as it always has.

CARS SPEED PAST as I drive back to town from the border. Occasionally a heavy, rattling logging truck lumbers by, moving too fast for its heavy load and the narrow, two-lane highway. The Northland Hotel and Lounge seems as good a place as any for a pit stop. Once inside, I pull up a stool at the center of the bar and order a Coke from the bartender. A shortish woman wearing a t-shirt tucked into her blue pants, she looks much older than any of the three customers present this afternoon. Her puff of curly, white hair accentuates a wrinkly, freckled face.

Shortly after I sit down, she asks me a question which I struggle to understand. Her accent is peculiar, a thick, almost slurring French Canadian.

“Did you come all the way from California?” she repeats, glancing through the window at my car’s front license plate.

“No. I came from Portland,” I tell the bartender, who introduces herself as Irene Gagne. “I’m in town to check out what life’s like so close to the border.”

Clumped at the end of the bar, all three of the customers look over from their conversation in curiosity.

“I’m trying to find Sherby Paradise. Some people from Customs told me I should try to find him,” I explain. “Do you know who he is?”

Turns out they know Sherby here. They look surprised that I might doubt that they’d know him. There have been a lot of Paradises in town, they tell me, and they know every one. They point out a framed picture by the door of Jay, Sherby’s deceased older brother. Jay watches over the bar wearing a fishing hat, grinning from behind a frazzly beard.

I glance back at the customers and focus my attention on one as he buys another round of drinks for his companions.

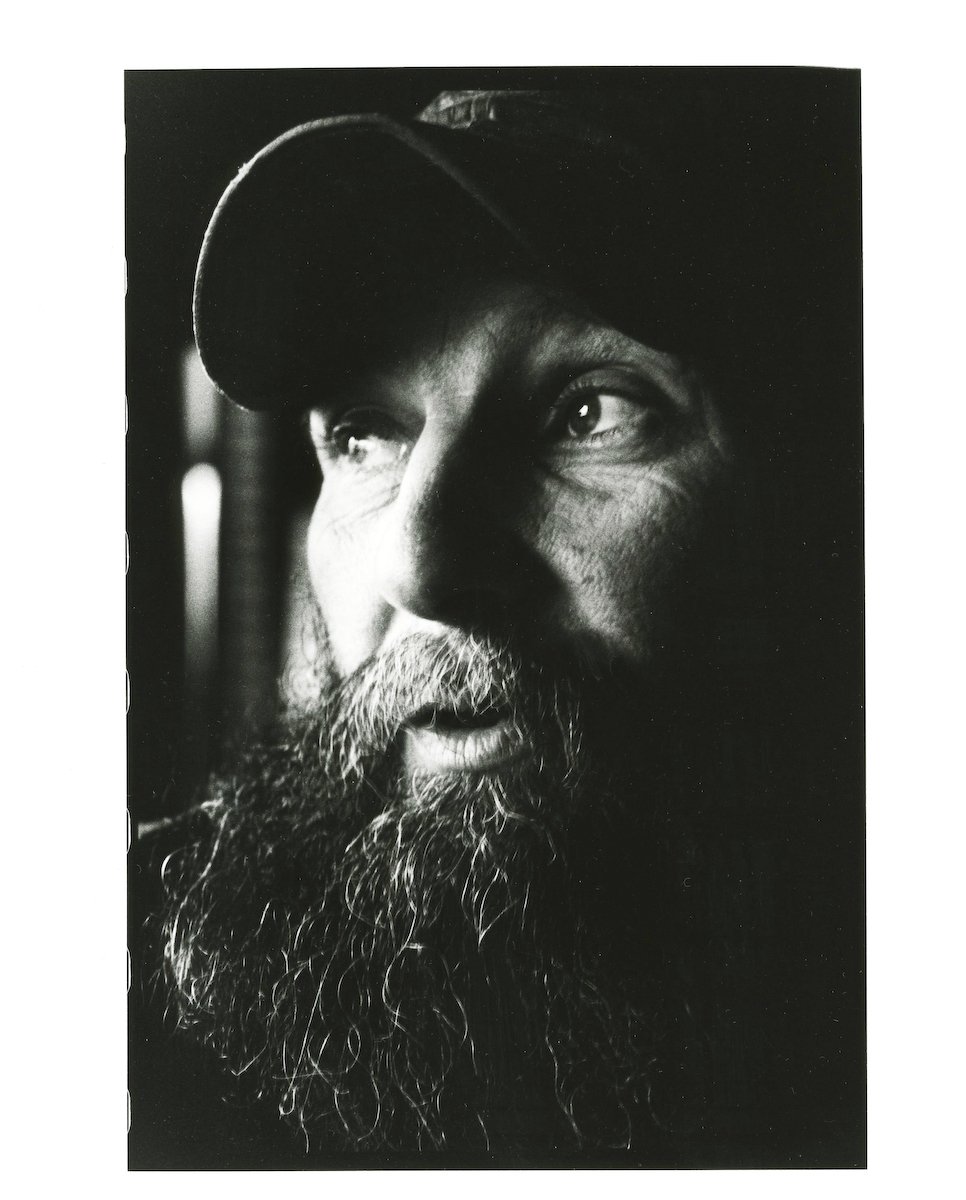

It is the day after his forty-sixth birthday and the celebrations haven’t quite ceased for Bruce Mercure as he finishes his Budweiser. Bruce wears an ancient, gray hat. It is so stained that I can barely read the words that say “Ducks Unlimited.” A lone, ragged feather sticks up from one of its sides. Lifting the hat for a brief moment, he reveals long, thick brown hair. Three or four shirts hide beneath a worn red and black-checkered flannel top layer. Dark gaps are interspersed among what yellowing teeth remain in his mouth. His bristly, tangled beard looks as if it has been growing for centuries, yet his blue eyes twinkle with youth.

Bruce says he loves it here.

He loves Jackman and the surrounding wilderness. Nonetheless, he quickly points out that he’s not a native. Born in Connecticut, as a child Bruce came up to Jackman every summer with his father, who was born here. He fell in love with Jackman on those trips, but remained in Connecticut to make a living as a carpenter and an electrician. Finally, fed up with a life he says became too hectic, Bruce moved to the area fourteen years ago in search of simplicity.

“You know, I finally have peace,” Bruce says. “I have peace with myself and I like living here. I like getting up in the morning. It’s comfortable.”

“THIS IS THE COMMUNITY OFFICE,” Vanessa Rancourt, one of the Northland’s bartenders, says one night after finishing her shift. She sits at the end of the “regulars” side of the bar, smoking Camels and drinking a Bloody Mary.

Margarette Pomerleau, the Northland’s owner, stands near the stairs to the cellar, surveying the bar while chatting with Vanessa and some regulars. Wearing a trenchcoat draped across her shoulders, she reaches into an inside pocket and pulls out a small twist-cap bottle of Sutter Home Cabernet Sauvignon. She pours the dark red wine into a glass and sips it on a night that’s rather busy for this time of year. This is the off-season. It’s getting too cold to canoe or fish, the hunting season has yet to begin, and the real money won’t come in until the snowmobilers start roaring into town in December.

The Jackman Hotel just up the road has a bar too, but it’s not open all year long and everyone considers the Northland to be the only bar in town. People don’t say “See you at the Northland” when they go out. They say “See you at the bar,” or even “See you at the office.”

Personal mail often gets delivered to the Northland. It’s not unusual to see packages delivered in the parking lot. Don’t know how to find someone in Jackman? Just mail it to the Northland.

No address.

No zip code.

Just “John Doe, Northland Hotel, Jackman, Maine.”

SITTING AT THE CENTER of the bar, Dave Paquette taps a salt shaker over his mug of draught Bud. Tiny grains explode in the beer, fireworks streaking fizzily through the amber liquid. Every bartender at the Northland hands Dave a salt shaker along with his beer whenever he first arrives for the day. It’s a French Canadian thing. Each glass, another shake of salt.

“Salt helps preserve ya,” Dave observes. He says it reminds him of the ocean.

“I’ve seen woodsmen and hunters back to back, five or six, the whole bar, just trying to get a beer,” Dave recalls. A Jackman native, he’s been coming to the Northland as long as he can remember.

“I think I drank everything on that bar at one point of time,” he says, pointing at bottles upon bottles of whiskey, rum, vodka, and other libations rising from the center of the bar like a mountain range stretching toward a sky of flashing white Christmas lights.

Dave even witnessed a defining moment in the Northland’s history, the legendary blaze that destroyed the old Northland.

Built over 100 years ago, the Northland had long been a Jackman institution when it burnt in 1984, four years before Margarette bought the place. The building had just been re-wired a month before the fire started in one of the upstairs rooms. Despite rumors that spread after the catastrophe, nobody seems to think that the fire was suspicious. Even so, like many events that have happened through the years, there are different recollections of what happened.

“If the walls had ears then they’d be able to tell you different stories,” Dave says of the fire’s origins. His version, however, is the version that other witnesses remember as well.

“It was dripping fire out of the ceiling,” he recalled. The fire started upstairs in one of the hotel rooms, he says, but nobody realized it until flames started coming through in the far corner of the bar. “Once it got in the walls, in between the floors, there was nothing they could do to stop the fire. Nothing.”

After the fire started, Dave went upstairs to make sure nobody was in the rooms. Fortunately, everyone made it out alright. Overwhelmed by the smoke, he came back downstairs and caught his breath outside. Someone else had driven a truck up to the door, and Dave helped people move everything out as fast as they could, including a bunch of mounted animals killed by hunters over the years. There were bears, deer, coyotes and even a bobcat. Not everything could be saved, but what was still hangs in the Northland today.

“THAT MOOSE there’s been shot so many times it’s unreal,” Margarette says, pointing to a huge mount on the wall, adding quickly “by the camera.” People come in all the time because they’ve heard there’s a moose there and want to know if they can have their picture taken with it. She thinks it’s ugly, and points out that its antlers aren’t even identical.

There was a mounted moose in the old Northland when it burnt. The owner at the time rebuilt the Northland just two weeks after the fire but never replaced the Moose. When Margarette bought the bar, people kept asking her to put a moose back in. Finally she relented.

“It was road-kill, by the way,” She declares “I didn’t have it killed.”

Lucky find. But it’s the kind of touch that seems to draw people into the Northland, and it’s also a sign that Margarette respects the aspects of the bar’s heritage that came before her. “This is what people want. I don’t particularly care for the looks of this building, but this is what people like. I didn’t build it. Thank goodness I didn’t build it, because it wouldn’t look like this, and it probably would not be as profitable either. People like to come in here.”

For Margarette, it’s all about what the customer wants. “It’s not what you like. It’s what they like.” One thing they like is the friendship, and Margarette does what she can to keep up with the customers. Whenever someone comes in the bar she hasn’t seen in a while, she asks about that person’s family and life. She makes customers feel comfortable and there’s a sincerity and warmth in her tone that suggests that she genuinely cares.

“How many bars do you go to in Boston or out of state people talk to you?” she asks. “The person sitting next to you at a bar is not going to talk to you. No way. It’s not going to happen. Here people turn around, they’ll strike up a conversation.”

Whenever Margarette travels, she ends up missing the activity at the Northland. Although she enjoys visiting her three sons, who have all moved away from Jackman, she says the low key trips can become too much for her. “After 10 days of that I’m ready for noise,” She says, “and people around me.”

Not all of her trips have been comfortable, either. Once Margarette was traveling in Missouri and went to a bar. She ended up being the only woman there. It was creepy and she says she felt unwelcome. After buying the Northland, she decided that she didn’t ever want a woman to feel the way that she did in Missouri. Now she makes it a point to maintain a space where women feel as comfortable, safe and welcome as men.

“Every customer here is special,” Margarette explains. “Not everyone, the majority are. Let’s put it that way.” Refining her point, she adds, “There’s some that are not, but overall, 99.9 they are. Troublemakers are not. And they know who they are."

Margarette’s efforts to create a welcoming atmosphere are also rooted in family tradition. The daughter of Armand Pomerleau -- the legendary proprietor of Pomerleau’s General Store in nearby Long Pond -- Margarette runs the Northland with a warmth and generosity that she learned growing up and working in her father’s store. A separate fire destroyed Armand’s store in 1988, a few months before Margarette bought the Northland. After that blaze, Armand didn’t have the energy to rebuild his store

Bruce thinks that one of the reasons Margarette bought the Northland was to carry on her father’s tradition after the fire at his store. A sign stretching across the front of the Northland is a physical link to that tradition. The sign reads “If you don’t stop, smile on the way by.” That was a slogan Armand Pomerleau thought up years ago to welcome people to his store. After the store burnt down, Margarette brought the sign to the Northland. People still remember it from the days when it was in front of Pomerleau’s General Store. They tell Margarette they’re glad she kept it and put it up at the Northland.

This work is in Margarette’s blood.

“I’d probably miss it if I left it,” she admits, although she doesn’t speculate about what the future might bring. “Because I’ve always been around people. I mean, I just couldn’t go work in an office. I’d go out of my mind . . . doing anything besides being with the public."

People wanted to be with somebody [on Sept. 11]. They didn’t want to be alone. They all came in and watched TV together. You could hear a pin drop.”

Margarette Pomerleau

Northland Owner

THE PEOPLE bring Raymond, “Gripper,” Griffin to the Northland. Just the people.

“I had a heart attack four years ago. I can’t even drink no more. So I come in and have a mixed drink of 7-Up and Coke just to be able to talk to people, people I like. I enjoy it. It beats the heck out of staying home and watching TV.”

A transplant from Bangor, Gripper has lived in Jackman for 35 years, a fact he is extremely proud of. Only deciding to stay after an exploding truck tire nearly killed him, Gripper says he’ll never regret moving to Jackman for good. “I couldn’t have picked a better place to live, I don’t believe. Ever.”

Gripper sits at the end of the “regulars” side of the bar, talking with Bill Cuddy, who works across the street at the Four Seasons restaurant and used to work in the Scott Paper Mill. Bill, who is much younger than Gripper, stands in his usual spot, a small space that allows him to look down the bar and out at the rest of the room. He frames nearly every explanation or affirmative statement with a “yup,” at both ends.

Gripper, whose iron handshake proves a well-earned nickname, glows with pride about just about everything. His choice to stay in Jackman. His children. And his hat.

He just got it tonight.

It’s black. On the front, large, white letters spell out NYPD. Along the side it says 9-11. He had been looking for a hat that said either NYFD or NYPD. His son Ryan, who works in New York, hasn’t been able to get one up to him.

Earlier on the same October night that I met Gripper, a man stopped at the Northland who had been at Ground Zero during the World Trade Center attacks. Months after the catastrophe, he returned to the site to watch the recovery of the last 22 bodies. It was the most horrible thing he’d ever seen. He told Gripper that he’ll never forget it.

Gripper told the man he was looking for a hat like his.

“I had on a Polaris hat and he says ‘I’ll tell you what, I’ll trade this hat for that Polaris hat,’ so he took it and I got this beautiful hat from the New York Police Department,” Gripper reflected, pulling his hat a bit tighter on his head, “I’m really proud, because I wanted one so bad, and to get one right from Ground Zero, boy that’s gotta be even more special.”

Inside the Northland, above one window the words “God Bless America” stretch in shiny red, white, and blue lettering on a string, like at a birthday party or a graduation. On the opposite side of the room, another string spells out “United We Stand.” Apparently the place was packed on September 11th after news spread about the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

“They were all in here that day,” Margarette says. “The place was mobbed. People wanted to be with somebody. They didn’t want to be alone. They all came in and watched TV together. You could hear a pin drop.”

The September 11th attacks prompted the federal government to begin building a new $20 million inspection station at the border. Personnel from as far away as Arizona and Florida are being transferred to work for the four agencies operating at the Jackman Port of Entry. There is not adequate affordable housing to accommodate this influx of new federal agents. Indeed, the new local supervisor for the Customs Agency has been here for a month and still hasn’t found a home. “There are a lot moving in,” Margarette says, “It’s unbelievable.”

A DOOR CREAKS OPEN and everyone looks up as a few out-of-town bikers walk into the Northland. Some regulars sit along the bar near the side door, a gentle sort of gauntlet that the bikers must pass as they stroll to the opposite side of the diamond-shaped bar, away from the side that instinct tells them is for locals. However, many of them have been to the Northland before, and all of them are welcome this afternoon, even if they are outsiders.

Clad in black leather chaps and vests worn over jeans and sweatshirts, the bikers mill about the lounge. Some head straight for the two pool tables. The others step up to the bar to order drinks. Waiting patiently at the end of the bar, this advance party announces that the rest of the pack is on its way.

Suddenly, the heavy rumble of approaching motorcycle engines shakes the walls of the Northland. Like an invading army rolling through town, the sound overtakes the bar. Inside, the murmuring trickle of bikers swells to a flood of riders spilling through the door. Irene and Vanessa serve bottle after bottle of Budweiser and pour rivers of cocktails. They are capable and patient with the rush, yet are grateful as Margarette steps behind the bar to lend a hand.

Margarette doesn’t seem to have any qualms about doing the grunt work. During the off-season, a good night at the Northland is usually about 25 people. This Saturday afternoon about 75-80 bikers show up at once for the second to last stop on the Solon 200, an annual charity ride from the town 50 miles to the south. They line up three deep at the bar, chatting about the cool weather as they shout advice to their friends playing pool. Margarette meanders across the bar picking up empty glasses and bottles, stopping to chat with people she hasn’t seen since the ride went through last year. A few of the bikers are playing horseshoes out back. One of them, Jim, the ride’s organizer, notices Margarette headed out to the porch overlooking the horseshoe pits and quickly spreads a message through the crowd. The bikers take a break from showing photos of their other motorcycles to each other and the rest of the bar’s customers. Pool games pause and the heavy clang of horseshoes momentarily ceases.

"Thank you Margarette!!!” the bikers erupt, sounding like elementary school kids at the end of a favorite field trip. She grins and acknowledges the crowd with a quick gesture halfway between a wave and a bow, but the humility fails to hide her excitement about the attention. After the empty bottles are cleared, she grabs a small camera to take pictures of the event. The pictures may eventually end up alongside shots of numerous Halloween and New Year’s parties that fill a stack of albums near one corner of the bar.

The bikers leave as quickly and dramatically as they arrived, buttoning leather jackets and revving engines. The ride is clearly a treat to the bar’s locals, who race to the windows and doorways to watch the Harleys speed away. Their giddiness is evident as they point at the different bikes and jump up and down to get glimpses. “Oooh, look, he’s going to make it smoke!” someone says, patting his neighbor on the back for emphasis. Sure enough, a huge cloud of gray smoke bursts out of a motorcycle tailpipe and engulfs the parking lot. Allowing time for dramatic effect, the rider lets the smoke dissipate and then throttles south along Route 201.

Margarette heads outside, eager to get a shot of each bike as it leaves. She races about in a long beige skirt and yellow Northland Hotel sweatshirt, her white tennis shoes somehow impervious to the dirt blowing about. The last bike is a three wheeler with a small rumble seat. Greg, its rider, motions at Margarette to sit down in back. She grins, but politely declines.

“C’mon Margarette,” the onlookers urge her to accept the offer, “We’ll watch the bar for you.” Bruce offers to hold onto the camera as Margarette sets aside her initial reluctance and jumps into the back seat. The 67-year-old woman looks like a 17-year-old heading out on a date with the class rebel. She throws her arms around Greg’s shoulders and the moment is captured in the frame forever.

Part II: People Fall in Love; Trees Just Fall

BRUCE MERCURE MOVED TO JACKMAN fourteen years ago in the middle of winter. He drove a van packed with all his gear. At 11:30 at night he ran out of gas near Parlin Pond, about 15 miles south of Jackman. Gritting his teeth, Bruce wrapped himself up in his sleeping bag, preparing for a cold night. As he settled in he saw headlights coming up the road, so he got out of the van and stuck out his thumb to get the passing car’s attention. A couple picked him up and brought him to the Northland, which was just getting ready to close.

Margarette was working. Bruce already knew her from his childhood trips with his father to Jackman, and so he told her about his predicament. They finished closing the bar at 12:30 and Margarette drove Bruce back down to his van with a can of gas so he could drive back to town.

“Only in Jackman can you do that,” Bruce says with a tinge of wonder. “That’s probably my favorite memory of this place, of Margarette. She’s been like family to me. Forever."

Bruce now lives in a camp – a seasonal cottage – that he converted for year-round use. Nine miles east of Jackman, it lies at the end of a lakeside settlement known as Long Pond. Many people who live in Long Pond work in Jackman, and many Jackman residents, such as Margarette and Sherby Paradise, grew up in Long Pond. Both communities lie within a wider region known as the Moose River Valley, where forests blanket the rolling hills and lakes and rivers carve valleys between them. It’s a 50 mile trip south along Route 201 to Bingham, the next town of any significance. Another twenty miles south brings Jackman residents to Skowhegan, where monthly pilgrimages are timed to include dentist visits, shopping at Wal-Mart, and perhaps even a trip to the movies.

Bruce is particularly attached to the natural splendor of the region, and he is eager to share the wilderness with his friends. His camp is surrounded by the woods, and the edge of Long Pond is only a few yards away, just past a set of railroad tracks.

I can still walk out in the woods with my son and take him out in the woods and teach him about the woods. It's like a never ending classroom out there.”

Bruce Mercure

Master Maine Guide

Nine miles is a long commute in a place like the Valley, especially once winter sets in. For Bruce, getting to and from Jackman is a constant concern. Four years ago he was caught drinking and driving twice in one month and lost his license. Through next August, when his license will be reinstated, he has to walk or get rides from friends and family.

“I walk, and I deal with rides and everything else.” Bruce says “I deal with that, but I don’t bitch at anybody. It’s my own fault, and I’ll pay the penalties.”

Hanging next to the camp’s front door is a wooden sign with carved lettering that reads “Bruce and Josh Mercure.” Inside, a high scoring writing assignment taped to the refrigerator proves Bruce’s pride in Josh, the nine-year-old son he adores. Elementary school portraits hang on one wall and snapshots of a celebration for Josh’s youth softball team lie on the kitchen counter.

As a condition of a custody arrangement with his ex-wife, Bruce can’t drink when he is taking care of Josh. “You know, I just don’t drink when I have him,” Bruce says. It’s as simple as that. He values his relationship with Josh more than anything, even more than he values the wilderness. Fortunately, the two are not mutually exclusive.

“I can still walk out in the woods with my son and take him out in the woods and teach him about the woods,” Bruce says, adding that Josh also teaches him about the woods.

“It’s like it’s a never ending classroom out there.”

The Future of Maine's North Woods

Much talk about the future of Maine's North Woods has taken place since this story was first written. Reading through the lines, though, in some ways it appears the discussion about the nature of the lands hasn't changed since Whitney and I visited the woods eight years ago. Read some of the following stories to bring yourself up to date:- Roxanne Quimby: Controversy in Maine - Yankee Magazine

- New U.S. Park? Maine Bid Draws High Profile Debate - National Geographic News

- Report urges North Woods collaboration - Mainebiz

- A Vision for the North Woods - Portland Press Herald

- The Maine North Woods - Terra Galleria Blog

- North Woods National Park - As Maine Goes

- Maine's North Woods at a Crossroads - National Resources Council of Maine

THE WILDERNESS SURROUNDING JACKMAN may not last.

Plum Creek, a large company from Seattle, Washington, has taken over the area’s once thriving timber industry. According to Bob Jirsa, the company’s Director of Corporate Affairs, in 1998 Plum Creek bought 905,000 acres of forest land from South African Pulp and Paper Incorporated (SAPPI). Much of this land surrounds Jackman and nearby Moosehead Lake. The purchase amounts to five percent of all land in Maine, and made Plum Creek the fourth-largest landowner in the state of Maine.

According to its own annual financial reports and promotional materials, Plum Creek adopted a new business strategy in 1999. It now looks for land that will be the most profitable regardless of whether it is more lucrative to produce timber or develop the land. Plum Creek maximizes its profit by cutting and selling all available timber and subdividing the cleared land to sell for development. After buying the SAPPI land for approximately $200 an acre, Plum Creek resold the land for as much as $1,333 per acre to private developers. It even profited from selling 65 acres to the state’s land trust system at $652 an acre.

In an article written for the October, 2002 issue of The Maine Commons, independent journalist Breanna Norris reported that Plum Creek maintains wood-cutting guidelines set forth by the Sustainable Forests Initiative that some consider controversial. Once Plum Creek’s largest customer, Home Depot was influenced by public opposition to these guidelines to stop buying lumber from the company. The guidelines require that only eight trees are left for each acre cut, Norris wrote, abandoning protections for old-growth forests. As a result, the article asserts, forests that have been sustainably harvested for more than a century are now diminishing. A recent Maine Forest Service analysis even shows that Maine’s largest landowners, including Plum Creek, are cutting 14 percent more land than the state’s forests are growing.

In addition to the clear-cutting, in the past decade the logging industry was decimated as local paper mills shut down and tree harvesting became mechanized. Tourism has emerged as the only major industry in Jackman. However, there hasn’t been a population increase parallel to the tourist industry’s boom, and Margarette laments that it is difficult to find people to work at the Northland.

Not far beyond the Northland, new houses are cropping up along the shore of Big Wood Lake, which forms Jackman’s western boundary. Built on Plum Creek land, these are not homes that the average waitress or bartender can afford. Most have been built by people from other states, such as New Jersey and Massachusetts. These are the type of people locals derisively refer to as Flatlanders. Combined with the new border project, these new developments have made construction the only secure source of employment outside of tourism.

“Everyone wants to move to Jackman,” Margarette says, talking about tourists’ first impulse when they visit. “Everyone,” she repeats. When and if they do, what will happen to Jackman?

“Portland is now a suburb of Boston. And they want to get away from that. What’s going to happen twenty years from now will be the same thing where they were at. They come up and they want to change things,” she says, adding “Where I used to know every single person now I don’t know half the people, because they all migrated from Boston, Portland, wherever”

Margarette insists that nothing will change simply to accommodate the newcomers. “We’re not going to change for them,” she says.

“IN SOME WAYS, we’re probably holding back a little bit from bringing big industry in, but I don’t think that’s what anybody wants,” Bruce once told me. “I think we all kinda want to keep it the way it is.

If nothing else, Bruce wants to keep his friendships the way they are. Friendships that are better than any he’s ever had. The kind of bonds embodied by the Six-Pack.

The Six-Pack is not just a tightly-knit group of friends.

It’s three couples.

Three couples deeply in love.

Three couples who came together at the Northland, and still meet there each time all six of them are in town. There’s Bruce and Molly Donovan, who lives in Northwood, New Hampshire and visits Bruce each month. Debbie and Steve Jenney are in the final stages of transforming their camp into a year-round home and moving to Jackman. And finally, there’s the newest couple, Karl Thomsen and Doris Audet.

As Bruce explains the Six-Pack to me at one of the Northland’s booths, Debbie saunters over behind him and makes bunny ears. After he catches her, she sits on his lap and whispers in his ear, kidding: “So Bruce, what role does the Northland play in your life?”

Irene, the bartender, notices the interaction and walks over to the table. “What is she doing here?” she chides jokingly. “What the hell are you doing with. . . .”

“Oh, you’re just jealous,” Debbie interrupts. Other people are milling about, laughing and poking fun at each other.

“Let’s get a picture of all my girls,” Bruce says, posing with Debbie and motioning for Molly and Doris to Join him. Karl comes over too, and Irene tries to stop him saying it’s only for girls.

“No, Karl, you can be in it,” Bruce allows. “I’ll let you share the girls with me.”

“Now do you understand why I come to the Northland?” he asks, surrounded by women.

Soon enough the group disperses around the bar. Debbie helps Irene wash some dishes. Molly heads back to the bar. Doris and Karl walk away, holding each other and giggling like it’s their first date.

Nobody tries to be something that they’re not. I think that’s what draws me to this community, because nobody has any aires. Everybody’s just down to earth."

Debbie Jenney

Six-Pack member

“I LIVED IN BELGRADE all my life. 53 years, and I have better friends here than I ever had there,” Steve Jenney, Jackman’s only plumber, says in anticipation of moving here permanently. “It’s my kinda life. I love to trap and hunt. A lot of people don’t like that. My town’s been overrun by Flatlanders. They’re taking Belgrade over. They wrecked my town. I hope they never do it to this one.”

Steve’s wife Debbie looks forward to moving to Jackman, even though she must quit a good job working for the Maine Secretary of State’s office. Like Bruce once revealed, she says she feels at peace in Jackman.

“Nobody tries to be something that they’re not,” Debbie says about the people in Jackman. “I think that’s what draws me to this community, because nobody has any aires. Everybody’s just down to earth. They’re just themselves.”

As I chat with the Jenneys, Debbie looks at Steve, who shyly tells her not to look at him. “Stop saying don’t look at me,” her voice turns from mock-scolding to affectionate and playful. “I like to look at you. It’s those suspenders and wool pants that really turn me on honey. That beard and that camo hat. That true sportsmen color. It’s a good thing you don’t have your Master Maine Guide patch on your sleeve there.”

Short and cheerful, Karl Thomsen looks like a back-woods hobbit, with round glasses, an eagle bandana wrapped around his forehead, and a long, braided pony tail trailing down his neck. He was the second person Bruce met in town, the first being Margarette. They were at the Northland and started talking about guns. Bruce had his rifle in the van and asked Karl if he wanted to go out to the parking lot to see it. They were getting along so well that Karl ending up inviting Bruce over to his house.

“We’ve been best friends ever since,” Bruce says of Karl. “He was the first local person that trusted me. Even though I’ve been coming up here for years he’s the first. You can come and you can be accepted but to really trust and to fit in you’ve almost gotta prove yourself, because so many people come and go. In the end he trusted me and he believed in me and we became friends and we started guiding together. We’re best buddies. Christ. Now we’re just, we’re just inseparable.”

After the photo shoot of Bruce and his “girls,” Karl and Doris invite me to their home so I could see all of their “old stuff.”

The two have known each other their entire lives, but only got together this year.

“It was awesome,” Doris says. “That is a love story right there. Him and I.”

“I was smitten with her years and years and years ago,” Karl admits. “It goes all the way back to Armand Pomerleau’s store, when she had a brown blouse on. I’m a nice guy and I don’t really push on, so she didn’t notice for a long time.”

Karl has a look of delighted relief when he tells the story. After thinking of her for such a long time, he finally had the chance to ask her out on Valentine’s Day. Now the two are all smiles. They still act like they just met, and the other members of the Six Pack say that both Doris and Karl seem happier than they’ve ever been.

They’re eager to show me their upstairs bedroom, which is warm, small, and comfortable. A number of items adorn the room: a knife made in the twenties by Karl’s uncle, a rug made by Doris’ mother, a banjo and a flute, some snowshoes, and a variety of eagle and turkey feathers that the couple is proud to say are illegal. Karl’s “main hunting gun,” a .30-30 made in 1905, hangs on a rack of carved wooden ducks.

More company arrives as they show off the different treasures, and Doris heads downstairs to greet the guests. Karl sighs after she’s gone.

“There are a lot of memories in here,” he says. “A lot of love.”

The room falls silent. Karl sits on the end of his bed, staring into the distance. Billy Joel’s “Uptown Girl” plays in the kitchen. It sounds so far away. The sobriety of the moment is a marked change from earlier in the evening

“I gotta go guiding the day after tomorrow,” Karl says somberly. This is the first time since he and Doris fell in love that the couple will be apart. It will also be the first time in years that Karl will guide alone. Since meeting Bruce, the two have always led guiding trips together. This year, however, Bruce cannot afford to take the time off from his construction work.

Karl, who has been guiding since 1978, describes this work as bringing ignorant people into the woods to take care of them. It definitely pays the bills though. His customers are nice, but it often feels like he’s babysitting. First, he spends a week setting up hunting platforms in the forest. Then he brings tourists out into the woods to help them find deer. Each night, he helps them set up camp, then heads home to bed before returning early in the morning for the next day’s hunt. He is only able to spend time at home on Sundays, when hunting is prohibited in Maine.

“It’s like holy mackeral.” He pauses, “No, no, it’s like holy fuck. I’ll be in the woods for six weeks.”

WILDERNESS GUIDING REMAINS one of the proudest professions in Jackman. For many locals who are intimately familiar with the surrounding wilderness, guiding tourists on hunting and fishing trips is a welcome supplement to their income. Just about every other person you meet sitting at the Northland’s bar seems to be a Maine Guide. Everyone else has a friend who’s a guide, or is married to one, or just knows an awful lot about the woods anyway.

While guiding can sometimes feel like babysitting, it also can be a rewarding experience for both client and guide.

“Most of the people I guide, I become friends with,” Bruce says. He jokes that he loses money because he ends up taking his new friends out. “The majority of the people I do that with, and that’s a good thing.”

One of the lifelong friends he has made through guiding is George Chapdelaine, the CEO of the Boston Restaurant Associates, which owns a chain of popular Italian pizzerias in the Boston area. Karl and Bruce guided him about ten years ago. Now George returns to Jackman every year with all his cooks for trips with Karl and Bruce.

“We’re just really true, good friends. That’s what I get out of it” Bruce says of the relationship that has developed with George. “It’s not the fact that I’ve chummed with a millionaire. It’s the fact that I’ve got a good friend. He’s got a lot of money, but it doesn’t matter. He still would prefer to come here to the Northland for a week, sit and drink with all the people in town. He could take the best room in town and buy it for a year, but he doesn’t. He comes and stays on my couch, you know, because that’s what he likes to do. I’ve met some super, super people guiding.”

THAT EVENING I leave Karl and Doris to head to Bruce’s house for dinner, where I spend the night hanging out with him and Molly. This isn’t one of the weekends that Josh is at the camp. The cans of Bud on the counter tonight make this evident. Despite his son’s absence, Bruce has been nearly giddy all day. It’s because Molly’s in town.

It’s late when the subject of the conversation turns to clear-cutting. Much later than Bruce normally goes to bed. Both of them have been drinking, but it’s more apparent in Bruce, who keeps dropping a cigarette as he tries to light it. It’s also clear in the anger and frustration in his voice, showing that he’s not so happy with the way things are going in the North Woods. The alcohol brings it to the surface, direct and sharp.

Molly, on the other hand, speaks with a different sort of passion. It’s not personal for her, although she expresses her dismay with as much outrage as Bruce. Besides the outrage, though, besides the information, there’s something else in her voice. Care. Tenderness. She expresses her point, while also recognizing Bruce’s anger. She holds her ground while simultaneously calming him, understanding him.

Bruce and Molly met twenty years ago. Sparks flew but they each were married to other people. As he puts it, they decided to “do the right thing” and wait patiently before “hooking up” three years ago, a good deal of time after their respective marriages crumbled. Now she’s planning on moving up from New Hampshire for good by next July, after her daughter graduates high school. Perhaps some day she’ll eventually use her 401k money to buy the lot next door to his camp.

That may be too late.

"When my son’s old enough, I hope we sell the whole place and move someplace else,”

Bruce declares. “Alaska. Australia. It’s not working for me anymore. You know, it’s like, it’s gotten so, grown up.”

Bruce sounds confused and frustrated that he’s not on the same wavelength with Molly. He recognizes that she still finds the landscape beautiful, while she realizes that Bruce feels his world is being polluted.

“It’s all gone,” Bruce laments. “It’s all gone.”

“But it’s not baby.” Molly tries to assure him. “You have to appreciate what we know, I mean, like, down in the lower, What do you call it? Down-river from here, it’s way worse. It’s still wonderful here.”

“But it’s not...”

She finishes his sentence, “...what it was."

“It’s not wonderful when you really look at it, you know?” Bruce presses his case.

“I know, I know what you’re saying,” Molly assures Bruce.

“It’s wonderful, because ‘oh yeah, great, I live in the land of clear-cut.’”

That word sets it off.

Molly unleashes a surprising torrent of anger toward the lumber companies.

“There’s policies where you’re supposed to plant as you cut. You’re supposed to plant as you cut. All the paper companies are supposed to plant, right?” No one really checks. There’s no way to regulate it, and there aren’t police enforcing that the paper companies do plant. Besides, Molly adds, “Around these parts you don’t want the police to come around. But the paper companies are supposed to do that. They’re supposed to plant a tree for every one they cut.”

“But they don’t do it,” Bruce interrupts, nearly screaming.

“They don’t do it,” she emphasizes.

“You said it perfectly,” Bruce assures “I could not say it any other way. She’s right. You know? They fucked with the woods!”

Part III: The International Bar Where Good Friends Meet

THE GREEN OF A ONCE VERDANT MOOSE RIVER VALLEY has been replaced by fiery waves of orange and red and yellow rolling over the hilltops. The annual moose-hunt comes and goes. Many hunters with permits to hunt in Region Two, which includes the Valley, descend upon Jackman. It’s a dress-rehearsal for the upcoming winter. While outsiders lucky enough to obtain one of the limited moose-hunting permits pack the hotels and line-up outside of Bishop’s gas station to weigh their kills, Jackman residents spend the week bird-hunting. Partridge season has just started too. It lasts for months and you don’t need to win a state-wide lottery to get a permit like you do for the moose-hunt.

By the weekend of Columbus Day the trees are nearly stripped bare. The drive from Portland feels longer, grayer, colder. Temperatures drop 10 degrees between Skowhegan and Jackman. Margarette and others have urged me to return for the last horseshoes tournament of the season. I am eager to observe one of the Northland’s much talked about events, my interest piqued by flyers in both English and French advertising the event. They are posted throughout Jackman and in other towns in the region.

Sherby Paradise arrives at the Northland about a half hour after the tournament ends, striding confidently through the room, wearing a beige trench-coat and a slick black hat encircled by a huge brim. He greets his brother, George, and his old friend Clem Achey, who both competed in the horseshoes tournament this afternoon. Everyone in the bar recognizes Sherby instantly, and vice-versa. He even nods at me knowingly as he passes. Minutes later, Margarette comes over to me and points him out, “That’s Sherby. You’ve been wanting to talk to him, right?”

Hypnotized by his self-assured entrance, I walk over to where Sherby is playing pool with Clem, George, and a number of other people. I introduce myself, and Sherby says that he’s heard I’m in town. He regales me with stories about Jackman, but interrupts himself periodically when it’s his turn to shoot. The tales compete with rock songs playing from the Jukebox and the glassy ricochet of pool balls rolling across a felt table. From time to time, George playfully barks at Sherby to stop talking and shoot. A dozen or so other people, many of whom were competing in the horseshoes tournament, are now either playing, or raptly watching, the game of pool. Most of them are old men. Many are drunk. They all seem quite happy. Playing against Sherby’s team of locals, an out-of-towner named John Pierce, labels his opponents “The Jackman Boys.”

Proud of this description, Sherby tells a story that he says illustrates the reputation of “The Jackman Boys.” A couple sentences into the tale he excuses himself, peers at the pool table for a few seconds, and sinks three beautiful shots. Many of the onlookers cheer, a few others groan. Taking a sip of his beer, Sherby steps away from the table and finishes the story.

One day he was driving into Quebec when he saw a pretty girl tending a cow near the side of a road. He struck up a conversation. Eventually the girl’s mother came out and told her to get back in the house. A few minutes later, the girl still hadn’t gone back. “...The mother came back outside and yelled ‘Where did you say that fellow was from?’ ‘From Jackman,’she says. The mother says, ‘You get up here right now, AND BRING THE COW!’”

NOVEMBER ARRIVES with a blanket of snow. Deer hunting season just started. Bright orange is back in fashion. This time the vests and the caps contrast sharply with the snow. I poke my head in to the bar to say goodbye.

My brief stop stretches into an hour. The light is falling. Four or five men walk in, all prepped to go deer hunting. One introduces himself as Bruce’s cousin to a man wearing a hat that says, simply, “Jackman.” In turn this man introduces himself as Bruce’s boss. The cousin and his companions are making a run to town for supplies. They’ve left Bruce and the rest of his hunting party camped down the road near Parlin Pond, where Bruce ran out of gas fourteen years ago.

It feels like a family reunion. The whole bar exchanges greetings and introductions.

This is the Northland.

Before I leave, I reach my hand into a fish-bowl stuffed with colorful matchbooks. Mine is red. On one side, it reads “An international bar where good friends meet."

On the other: “If you don’t stop, smile on the way by.”